The restaurant hustle

How Baton Rouge's growing food scene is adapting to the increasing challenges of running a restaurant

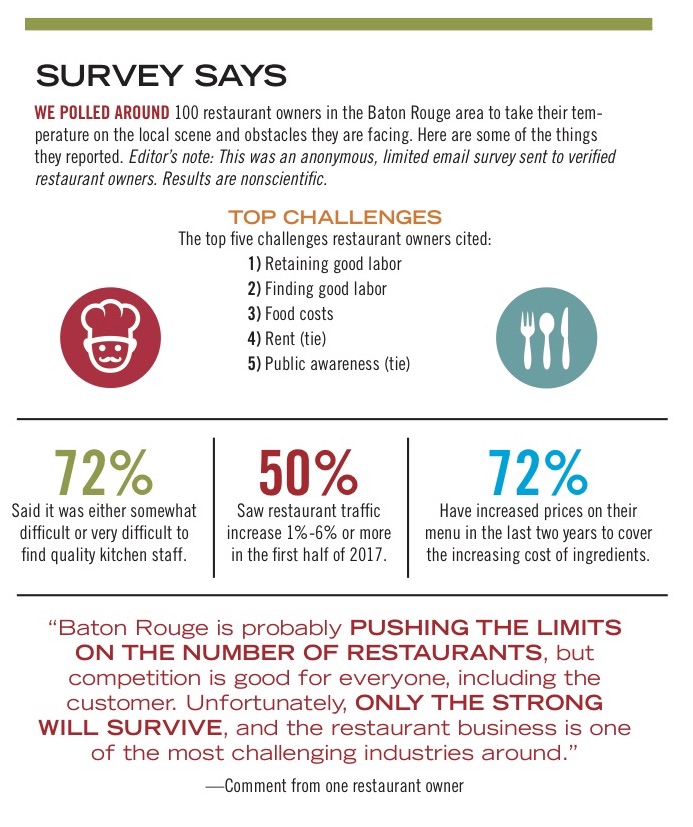

Restaurants in major cities across the country are struggling to adjust to labor shortages, rising food costs, steep rents and the expectations of modern diners who are one click away from posting a damning Yelp review. Some are downsizing, some are shutting their doors. Others are turning to catering, special events and delivery apps like Waitr to squeeze out more revenue. We wanted to find out: Is Baton Rouge’s growing restaurant scene heading in the same direction?

The parking lot at BRQ Seafood & Barbeque is, as millennials would say, lit with a September lunch crowd. The cars spill over into the lot next door.

Inside, though, there’s only a short wait. Chef and partner Justin Ferguson designed his deceptively large new restaurant to handle more than 180 patrons in the airy dining room, adjoining bar and the wide porch out front.

|

|

It’s been a packed house for lunch and dinner since opening in June, and the crowds haven’t let up months later, drawn to Ferguson’s competition-style barbecue meets gussied-up Southern cuisine.

For Ferguson, a homegrown talent who worked at Stroubes, Superior Seafood in New Orleans and for a corporate restaurant group in Chicago before returning for what he hopes will become a longstanding favorite, this was a gamble.

The intersection of Jefferson and Airline highways isn’t exactly a foodie destination or the next trendy neighborhood.

The menu is broad. We’re talking boudin balls next to kale salad next to barbecue platters next to an intriguing smoked octopus small plate broad. Clearly, the mantra of being everything to everyone isn’t lost on Ferguson.

“The menu is a little bigger than what I would do in a bigger city,” he says. “I don’t want you to come in and look at a small, one-page menu and go, ‘OK, great. There’s only one thing on here for me.’ I want you to be able to come back numerous times and try different things. I want to be here long-term.”

—BRQ’s Justin Ferguson, photographed while the restaurant was under construction in April. Photo by Collin Richie.

Know your market

Back in April as BRQ was buzzing with construction crews, Ferguson was next door in a cramped, makeshift office at Louisiana Culinary Institute scribbling all over drafts of the menu and considering the direction the city’s restaurant scene was heading.

Himself an LCI grad, he partnered with some of its top brass for a restaurant concept independent of the culinary school—though they are adjacent properties—and started strategizing.

First came some field work dining out at his local competition.

“I looked at everyone else’s prices, and quite frankly, I think everybody else’s prices are too high,” he told 225 then. “A lot of the prices here are the same as on menus you see in Chicago, which is crazy and it doesn’t have to be. But I think it’s just because people get used to that.”

His goal with BRQ’s menu was to straddle the line between casual and upscale while still offering generous portions. “You can spend money here,” he says, “but you can also come here and get a $12 lunch and get out.”

For an executive chef accustomed to working in corporate restaurants, Ferguson is now the face of his own brand, joining a recent trend of chef-driven restaurants that have energized the dining experience in Baton Rouge.

For an executive chef accustomed to working in corporate restaurants, Ferguson is now the face of his own brand, joining a recent trend of chef-driven restaurants that have energized the dining experience in Baton Rouge.

Just a few years ago, going to dinner in the Capital City meant chains, fried seafood platters, Cajun staples in every shade of brown and, as one longtime industry fixture told us, the same old special of “a piece of fish topped with some stuff and finished with some stuff.”

Today, we’re embracing seasonal menus, small plates, shared plates, greens grown on a nearby farm and an attention to detail that’s being matched by a younger and increasingly picky Food Network-trained clientele that follows the chefs on Instagram and expects every restaurant to be on their #supportlocal game.

While we are usually slow to national trends—sushi took a while to catch on here, and the bottom hasn’t fallen out yet for the cupcake market like it has in bigger cities—we’ve started embracing that idea of locally focused, chef-led restaurants.

“We probably have more unbelievable chefs in the market now than we’ve had in a long time,” says Dori Murvin, Beausoleil’s floor manager and a longtime restaurant professional. “The ones that are chefs right now, they really did go out and actually work up to this.”

Former City Pork Chef Ryan André, Curbside’s Nick Hufft, Beausoleil’s Nathan Gresham and Kalurah Street Grill’s Kelley McCann, as well as food personality Jay Ducote, have been elevated to celebrity status here in part because they’ve played the face of Baton Rouge’s culinary scene on TV, in competitions and through flattering local and national media coverage.

At press time in mid-September, we were watching a USA Today story calling Baton Rouge one of “five underrated food cities in the South” make the rounds on social media and through a Visit Baton Rouge email blast.

Yet with that breathless focus on the hot new chef, the newest food trend and the next foodie destination, it’s often hard in larger cities to keep up with the pace, and new restaurants step into the fray as quickly as another one bows out.

In New Orleans, The Times-Picayune counted 27 restaurants that shuttered since May this year. The newspaper’s food writer questioned if this was a doomsday scenario, though 15 other restaurants had opened there around the same time and several others were about to launch. Some commenters chalked this up more to the cutthroat market and a summertime slump than a burst bubble.

Earlier this year, The Chicago Tribune reported that independent restaurants nationwide fell by 4% in 2016 while the fast-casual eatery segment rose by 7% (more on that trend later).

In Baton Rouge’s smaller scene, restaurants don’t usually come and go so quickly. But from 2016 to now, we saw the opening of more than a dozen exciting new restaurants like Eliza, Cocha and Ava Street Café.

And in early 2017, two buzzed-about restaurants bowed out after only a short go: Table Kitchen & Bar after two years and Goûter after less than a year.

The two closures together don’t mark a trend, but it’s worth noting both were small independent restaurants heralded for their innovative focus and, in news stories, owners cited the stress of running a restaurant as reasons for closing.

Despite the similar gamble for BRQ, it has the experienced backing of some of LCI’s brass and an executive chef trained in the corporate model. Still, expectations were high for Ferguson’s restaurant as he prepared to open in June.

“You always get nervous,” he told us the week before opening. “This is the 10th restaurant I’ve opened, but it doesn’t matter—you still feel like you’re going to throw up every morning when you wake up. We’re relying on 100 other people doing their jobs correctly, so that’s the stressful part that you only have so much control over. … We’re opening up full steam and really showing all our cards day one. So really, opening day is no turning back.”

Everyone’s a critic/everyone’s a chef

The popularity of cooking shows, though it might seem trivial to some, has changed the way we experience fine dining. For one, we’ve become armchair food critics, pulling from those shows a misplaced understanding of how the food should look. For another, we’ve all decided we could totally open our own restaurants.

“There’s a romantic story being told by television that is a completely different reality from what’s really going on in our industry,” says Charlie Ruffolo, LCI’s director of public affairs and a BRQ partner.

The success of those shows means more people are inspired to follow their dreams of a culinary degree. Ruffolo says with only about 36 students admitted per semester and no plans to expand that scope, LCI has had to tighten up its admissions process.

The school has also had to instill in new students an understanding that the restaurant industry is intense, and they’ll need to start from the bottom in the kitchen and work their way up.

“We’ve had to change our way of teaching to reach that same student,” says LCI Director David Tiner. “It’s about getting beyond the ‘I want it now’ syndrome—I want to graduate from culinary school and open up my restaurant two days later, or just walk into a restaurant as the executive chef.”

“We’ve had to change our way of teaching to reach that same student,” says LCI Director David Tiner. “It’s about getting beyond the ‘I want it now’ syndrome—I want to graduate from culinary school and open up my restaurant two days later, or just walk into a restaurant as the executive chef.”

Ruffolo says the key is setting them up for success and showing them other options in the industry, like food sciences, test kitchens and hospitality. “It is attractive to come in right now and become a chef, and be on the line figuring stuff out, but in the same breath, it’s a ton of work.”

Restaurant owners show up for job fairs at LCI and local community colleges, but experience has taught them a culinary degree isn’t enough to run the kitchen. Owners interviewed for this story say their kitchen staffs are a mix of culinary graduates and workers who started in dishwasher-level positions. Others say some of their best have come through word of mouth.

“A lot of them get disillusioned that they are going to come out [of culinary school] and run everything,” says Jim Urdiales, whose Mestizo Louisiana Mexican Cuisine has been at its Acadian Thruway location for more than a decade. “But you’ve got to earn your chops. I’m not turning my kitchen over to some young person just because he went to culinary school. I need to see that you can handle the pressure, execute a plan and be creative.”

Keep it casual

Keep it casual

The rise of fast-casual restaurants has made customization king. Falling somewhere between fast food and a sit-down restaurant, they tout fresh ingredients and local products you can mix and match. The experience is meant to be more familiar than corporate and healthier than prepackaged.

The local minds behind businesses like Street Breads, Lit Pizza, The Salad Shop, Izzo’s Illegal Burrito and, most recently, Southfin Southern Poké, have all found success with the concept.

Nationally, the fast-casual trend has influenced major chefs to downsize their traditional, white tablecloth restaurants and offer more approachable menus—some even abandoning the brick-and-mortar altogether for food halls and food trucks. Local restaurants are responding in a variety of ways.

The team behind Juban’s unveiled the more casual Adrian’s in September. New Orleans-based Copeland’s launched its Batch 13 prototype on Essen Lane earlier this year, serving up pastries, breakfast and lunch in a modern space with communal tables.

—Mestizo owner Jim Urdiales

Galatoire’s Bistro had trouble shaking the image of its stuffier New Orleans sister, so owner Melvin Rodrigue renewed its vows to casual eating in 2016 by combining the lunch and dinner menus.

Fast-casual has also brought on the bowls trend: poke bowls, grain bowls, breakfast bowls. At Mestizo, Urdiales says his colorful protein bowls have outpaced sales of more traditional Mexican fare.

In more subtle ways, new restaurant design is taking cues from the fast-casual trend, which puts ingredients and food prep front and center behind the sneeze guard. Downtown’s Cocha and The Gregory have staff prepping cuisine in kitchens open to the dining rooms.

When the owners of Zorba’s Greek Bistro returned to Baton Rouge from a 12-year hiatus in their native Greece, they ditched their former fancier digs for a smaller space in an Essen Lane shopping center. Four years into the new location, they are finishing up an additional kitchen with a large window for views of all the behind-the-scenes activity.

“Our success came because people were open to trying new things,” says Zorba’s Dino Economides. “We were the first Greek restaurant in Baton Rouge, and so moving from the more traditional setting that we had into the bistro setting has made it more modern.”

Getting over the hump

Getting over the hump

It’s 3 p.m. on a September weekday at BRQ, and Justin Ferguson is huddled at a bar table with his managers. They all have their laptops open and look like they might be furiously arranging fantasy football leagues. But they are instead using this downtime before the after-work crowd kicks in to organize staff schedules and review spreadsheets to see which menu items are selling and which aren’t.

“We go through it and study it and rethink what we’re doing,” Ferguson says.

He’s also considering what’s next, now that he’s gotten through the first three months. He’s planning to ramp up catering again—something he was doing before BRQ opened to drive interest.

Many restaurateurs interviewed for this story have utilized catering to add profit, realizing the dining room alone won’t cut it. They’ve embraced booze as well. Even for classier joints, a wine menu isn’t enough anymore. It takes a wine menu, plus a craft beer menu (the more local the better) and a slew of seasonal cocktails to get young professionals in the door.

Sometimes, they are getting in the door just to pick up to-go orders, or sending Waitr or UberEATS to get it for them.

“There’s always going to be a need for a personal touch and the experience of getting out of the house,” Urdiales says. “But I think our industry is still in for a really big shakeup. You can’t get comfortable, even once you’ve had your first year. Now that you know who your clientele is, you have to start thinking outside the box.”

For Ferguson, he’s feeling fortunate for BRQ’s success so far, though he admits to being scared every day that something will go wrong. “But it’s finally getting to where for the first time I haven’t had to work the line [in the kitchen], and now I’m finally getting everything else caught up.”

After just three months and all those spreadsheets, Ferguson has tweaked his menu seven times. Is that excessive? Probably. But as he says, “it’s because we’re trying to listen to our guests. At the end of the day, it’s not about what I want. It’s about what our customers want.”

“What I’ve learned over the last three months is that everything we’re doing is for Baton Rouge customers. But I think I’ll always continue to push the envelope a little bit and say, ‘Let’s try it. Let’s see if it’ll work.’ And if it doesn’t, then let’s move onto something else. I think it’s important to keep doing that and continue educating our guests and our staff with new ideas, new food and new techniques.”

So, gone is the burrata and caviar appetizer; hello to a few more traditional fish dishes topped with beurre blanc or crawfish tails. He’s also had to raise the prices a little on his steak menu to compensate for food costs.

But that smoked octopus small plate even Ferguson wasn’t sure would catch on? Still a winner. [225]

This article was originally published in the October 2017 issue of 225 Magazine.

|

|

|