A photographer’s images examine Capital Region food deserts and rural farming

In July, the Main Library at Goodwood hosted a second exhibit focusing on social justice themes. Bruce Q. Williams’ “Debut” show featured visuals from two separate photo stories. Here, Williams shares the inspiration behind them. His answers are edited for clarity and brevity.

How did you get interested in photography?

When I was a kid, my parents kept their cameras on the top shelf in their closet. I would always sneak up there and get a camera. But I didn’t start really taking photos until about five years ago. I took one photography class at BRCC, and I would always stay after class and ask my professor, Matthew Morris, a bunch of questions about composition and different styles. He mentioned that he thought my photography was good, so I started to take it more seriously. Later, I was working at Atomic Pop record shop with the owner Kerry Beary, who had been an art teacher in New York. We had a bunch of art conversations, and I got more familiar with the nuances of what I wanted to photograph. I started taking photos of local music shows and eventually made the switch to photography full time. I learned how to develop film from a roommate.

|

|

Do you shoot primarily on film now?

Yes. I develop film in my kitchen. I thrifted all my equipment, including my camera and a Nikon scanner from the ’90s that I use to scan all my photos. I like that film is not perfect. You can experiment with it more. I think visually it looks closer to what our eyes see in how it handles light and skin tones.

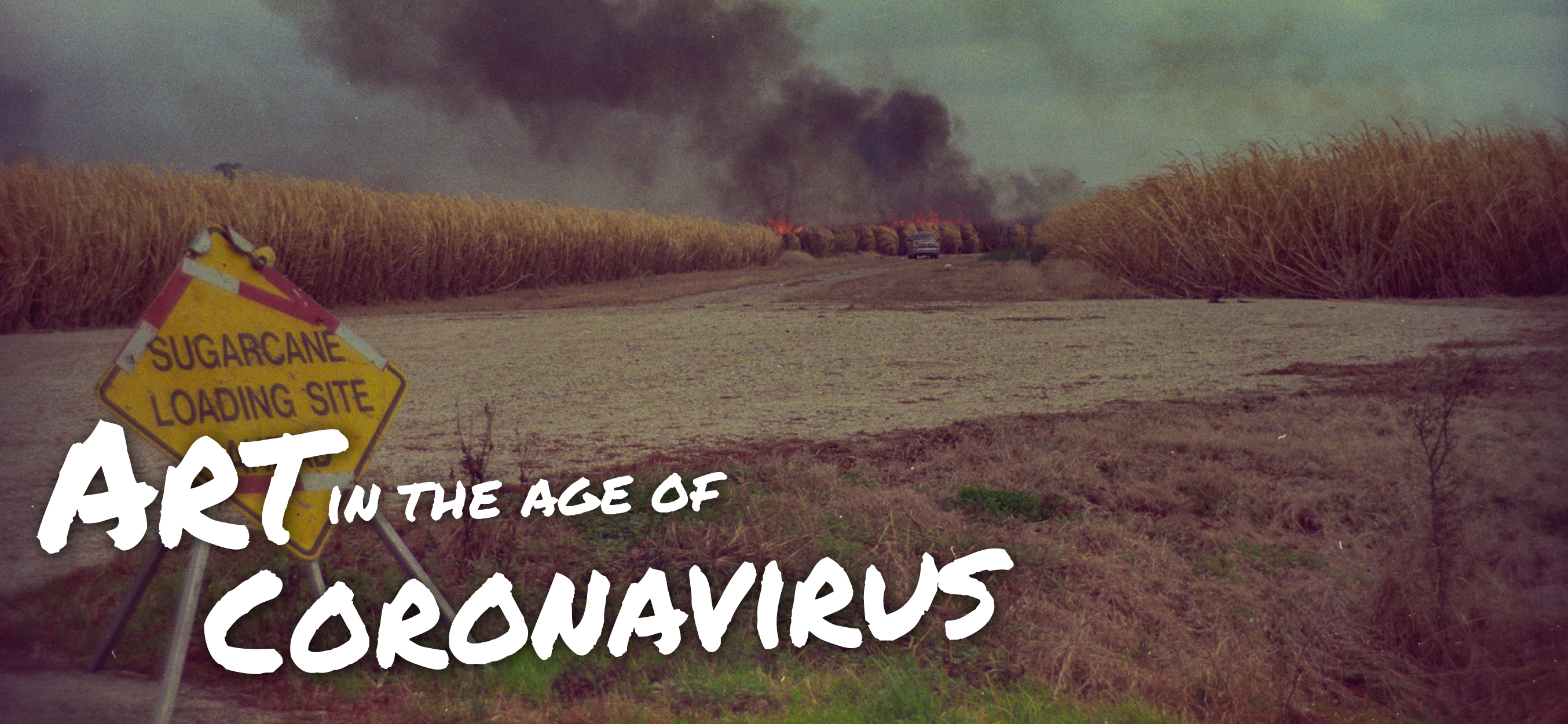

And captured on film, your “The Burning Bueche Sugarcane Fields” series is haunting. What’s the story behind those images?

After my grandmother’s funeral, my mom and I drove from Baton Rouge to the funeral home in Bueche to pick up some of her floral arrangements. On the way, we noticed sugarcane fields being burned. My family has been in Louisiana since the boat came over, and I’ve seen those sugarcane fields in that area my whole life. Seeing them burn was giving me goosebumps. When I got back to Baton Rouge, I went to the store to get some film and drove back to Beuche to photograph them. It felt very spiritual, like an out-of-body experience. Those photos, I think, resonate the most with the public out of any photo project that I’ve done. I’ve even sold some prints to people who don’t live here.

Why do you think those images captivate viewers so much?

Something about the fire is primal, it feels relaxing and comforting. And normally you don’t see a field on fire, but if you live in Louisiana you’re familiar with how things get cropped. It was fascinating to think that sugarcane fields have been harvested here for hundreds of years and are still being harvested. I thought it was a good way to showcase blue collar labor work that, who knows, maybe 20-30 years from now might become more automated. I think there’s a stigma about how intelligent or not intelligent farmers and farm workers are. But when most people make a fire, they don’t really know what the hell they’re doing. The fact that these farmers can control these burns on acres and acres of fields, and also have to factor in variables like the wind and nearby animals—a lot more goes into harvesting crops than people imagine. From an agricultural standpoint, it makes a lot of money for the state, but it doesn’t get as much attention as industries like tourism or football.

Your “The North Baton Rouge Food Desert Photo Project” showcases storefronts of small food marts and businesses owned by Black, Asian and Hispanic people. How did you put together this project?

My extended family is all from north Baton Rouge. Growing up, I always noticed the food marts. They were community safe spaces for people to catch up on local news and see family and friends. I kind of had a mental map of where all the food marts are, so I woke up early one day and drove out there to start shooting. I learned quickly that people will ask you a lot of questions when they see a camera, which changes the energy you’re trying to capture. I learned Sundays and Mondays were the slower days. So I’d wake up around 7 am, and I’d be able to photograph most of the spots on those days.

The photos are also meant to highlight food disparity in the city. What did it mean to have those images shown at the Main Library, where people from all different walks of life would see them?

I’ve always been a big fan of libraries, and showing them at the Main Library was kind of a random idea I had but didn’t think it was really feasible. But I pitched the idea before the pandemic, and it worked! I still can’t believe I really did that, now I’m thinking about it. When it came time to set up the exhibit, I didn’t want to make a big description of what a food desert is or put statistics. I just wanted to make people more open to and aware of how bad food accessibility is in north Baton Rouge, and how your environment affects your health. So for each photo, I included the proximity of where these food marts are from bigger grocery store chains in Baton Rouge. Most people don’t have to drive far to get food if they live close to these bigger stores. But that’s not the case for people in north Baton Rouge, because our city is so spread out, as well as because of gentrification, redlining and things like that. I’d actually pitched the sugarcane photo series to the library first. To be quite frank, I didn’t think the public would be that receptive to photos of food marts in north Baton Rouge. But the library was more excited about the photos than I was.

What kind of feedback have you gotten so far?

I’ve had a lot of people from north Baton Rouge contact me to say that they didn’t expect to see photos of north Baton Rouge in the library. And they didn’t expect to see photos that captured what it looks like to people who live there, from the beauty to the ugliness of it—like any environment we all live in. The library bought eight of the prints, and those will be in their special collections department archives. The prints they purchased were all of the north Baton Rouge food marts, which I thought was pretty cool. I thought they would have bought the sugarcane prints, but it meant more to me that they chose the food mart photos. From a history standpoint, I think it’s important to recognize people and communities that don’t necessarily get the attention they deserve.

How do these two photo projects connect and complement each other in the “Debut” exhibit?

I thought they were similar enough in that they were touching on contemporary social problems—food accessibility and farm workers, as well as the past history of farming in Louisiana beginning with enslaved people.

What does the name “Debut” symbolize?

It was my first solo show, and I started to realize the importance of having a show at the library. The significance of being Black and having your own photo show, even though I’m not trained in photography or social justice or activism. It’s also the name of an album I love by Bjork. When I was working at the record shop, we’d listen to Bjork every day. That album was released on July 5, 1993. That was the year I was born, and July 5 was my dad’s birthday—it felt meaningful.

What does photography mean to you today?

Photography has been an outlet for my anxiety and depression, and it’s really pushed me out of my comfort zone. I don’t think I really understand the magnitude of how my art resonates. And I’m starting to finally get that registered in my mind.

For more on Bruce’s upcoming projects, visit bqwphotography.myportfolio.com.

Check out more stories on art during the coronavirus here.

This article was originally published in the September 2020 issue of 225 Magazine.

|

|

|