More Black men stepping into leadership roles in Baton Rouge’s education systems

Correction: This article has been updated to correct an error about Baton Rouge Community College leadership. Philip L. Smith Jr. is executive director of Baton Rouge Community College’s Foundation—not the college, as was previously published. He also serves as vice chancellor of BRCC. Willie E. Smith was named chancellor of BRCC in May 2020. 225 regrets this error.

The tides are turning in the Baton Rouge area. Schools and higher education institutions that were in the past primarily led by white men now have Black men in executive roles.

In 2020, the Black Lives Matter movement sparked a national and global racial reckoning and conversations about representation for people of color. Entities from major corporations to large media outlets have added diversity committees, hired more Black employees and recruited people of color for top-level positions.

The shift toward more inclusivity has impacted the local community, as well. In Baton Rouge, it is especially evident in the steadily increasing Black leadership in education.

As of this summer, all major education systems in Baton Rouge are led by Black men. This includes Southern University President and Chancellor Dr. Ray L. Belton; Baton Rouge Community College Chancellor Willie E. Smith; East Baton Rouge Parish School System Superintendent Sito Narcisse, hired earlier this year; and, most recently, LSU’s new president William F. Tate, who was selected in May 2021.

Before Tate was named president of the state’s flagship university, LSU’s roster of former presidents and chancellors consisted only of white men. Though the latest census data shows that Baton Rouge is 47% African American, local leaders say they didn’t see comparable Black representation in educational leadership until recently.

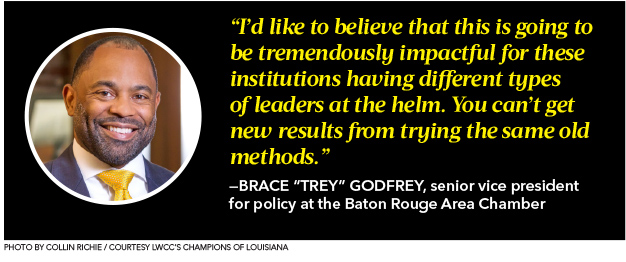

“Black males have been underrepresented in the highest levels of the education system for a very long time,” says Brace “Trey” Godfrey, senior vice president for policy at the Baton Rouge Area Chamber and former executive director of 100 Black Men. “It’s good to see them moving into these positions now.”

LSU’s newest president was selected from three finalists after a unanimous vote by the Board of Supervisors this spring. Tate’s career history, including a recent stint as executive vice president for academic affairs and provost at the University of South Carolina, made him the top pick. He is the first Black person to lead LSU and also the first Black head of a Southeastern Conference college in history.

“For me, this position is all about what we can do to help students and give people access and opportunity in higher education,” Tate said in an LSU press release. “That’s really in my DNA, how do we help people regardless of their background—we find the money, get you here and give you the opportunity to live your dream.”

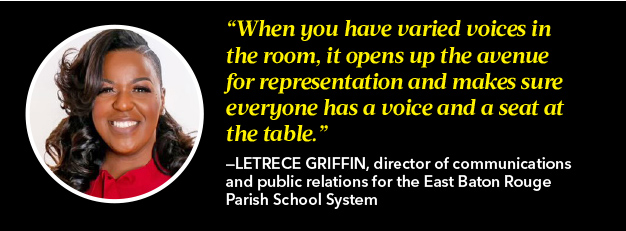

With more Black leadership in the Baton Rouge area, the potential for change, diversity and inclusivity is clear to local leaders. Godfrey and Letrece Griffin, director of communications and public relations for the East Baton Rouge Parish School System, say they are optimistic.

“When you have varied voices in the room, it opens up the avenue for representation and makes sure everyone has a voice and a seat at the table,” Griffin says.

While the change directly impacts local schools and the clout of higher education institutions, it has the potential to gradually influence other sectors, they say.

They imagine a Baton Rouge where Black children see Black men and women in the highest leadership roles, giving them the confidence to pursue a variety of careers in the future without fear of not having access because of their skin color.

“What young people see is what they’ll become,” Godfrey says. “Young students of color can look and see themselves represented in the very highest levels locally. It can open the minds of young people and perhaps even motivate them to strive for higher positions in education and even other areas.”

In East Baton Rouge Parish schools, the largest student demographic is Black—47% of students are Black and 43% are white, according to a 2014-2018 report by the National Center for Education Statistics. At LSU, diversity has steadily increased on campus, too, with the school’s trend data recording a 90% increase in Black, Hispanic and Asian student enrollment from the fall of 2010 to the fall of 2020.

“As activists and community leaders, you work so hard for moments like this,” Griffin says. “I don’t think it’s just one moment. I think there has been an alignment where people and society have been more open to hearing new voices and willing to allow the access to happen.”

“As activists and community leaders, you work so hard for moments like this,” Griffin says. “I don’t think it’s just one moment. I think there has been an alignment where people and society have been more open to hearing new voices and willing to allow the access to happen.”

Community leaders have worked for decades to see Black representation in leadership roles. Now with LSU and local education systems making headlines because of Black leadership hires, it opens the door to bigger discussions, such as whether more Black women will gain access to top-level positions, as well. There’s also the question of if hiring Black men for leadership positions is a temporary trend in response to the Black Lives Matter movement—or setting a new standard?

“The very bottom line of diversity is having people from different backgrounds bring different types of thought into arenas that they did not occupy in the past,” Godfrey says. “I’d like to believe that this is going to be tremendously impactful for these institutions having different types of leaders at the helm. You can’t get new results from trying the same old methods.”

This article was originally published in the July 2021 issue of 225 magazine.