After 79 years, Theatre Baton Rouge sits empty. What its stunning closure means for local theater

It was supposed to have been the seventh of nine shows in Theatre Baton Rouge’s 79th season. But the schmaltzy, upbeat roller skate musical, Xanadu, ended up being TBR’s last show ever.

On March 1, six days before Xanadu’s opening night, TBR’s board of governors abruptly announced the veteran arts organization’s closure. The nonprofit would neither stage the season’s last two shows, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Fiddler on the Roof, nor would it reach a landmark 80th season this fall.

“It was very emotional,” actor Don Fields recalls. The LSU junior theater major played Sonny Malone in Xanadu, one of several TBR productions he has acted in since arriving at the university two years ago. “TBR meant a lot to people in the local theater world. It was a big loss.”

DIGIT

6,000

Number of annual subscribers TBR had back in 1970, when demand was so high the organization kept a waiting list of prospective members. But over the past five seasons, these seasonal memberships decreased from 937 to 450.

The organization’s board of governors cited finances as the culprit, pointing to post-pandemic pressures that included declining ticket sales and soaring production costs. TBR’s shuttering took a notable quality-of-life amenity off the board for residents. And it served as a cautionary tale to other arts nonprofits.

“I never thought that I would see the closing of Theatre Baton Rouge,” says Playmakers of Baton Rouge executive director Todd Henry. “It’s always seemed so much bigger than the rest of our companies. And you know, if it can happen there, it could really happen to any of our theater and performing arts organizations.”

TBR’s demise has altered the region’s live theater landscape. Smaller organizations, some in existence for decades, have begun absorbing part of the role played by TBR, once seen as the area’s community theater hub. Its nearly year-round slate of shows allowed performers to partake in sweeping musicals, youth productions and provocative social commentaries.

“It’s a loss to the arts in greater Baton Rouge,” says Sullivan Theater founder Dave Freneaux, a past TBR board member and volunteer. “Absent TBR, there honestly isn’t enough stage and theatrical time in the community for everybody who wants to be involved.”

It follows a dismal national trend in which scores of organizations have closed since the pandemic. In 2020, theaters recorded nearly 90% declines in ticket income following lockdowns and social distancing, says Corinna Schulenburg, director of communications at Theatre Communications Group. The organization releases an annual Theatre Facts report on the state of U.S. nonprofit theaters.

Over the last five years, Schulenburg says theaters have overwhelmingly struggled to bounce back, facing other headwinds from declining attendance and inflationary pressures.

“It’s impossible to imagine a swift rebound from that for any kind of organization,” Schulenburg says.

‘No words’

It was the morning of the Spanish Town Mardi Gras Parade. Revelers were vying for pink beads and snapping suggestive selfies at one of Baton Rouge’s most raucous annual events.

The distraction didn’t keep scrollers from noticing TBR’s surprise online announcement late that morning. Gutted fans—including past performers, patrons and volunteers—flooded its social media with plaintive responses.

“Such a big loss for Baton Rouge,” “heartbreaking on so many levels,” “no words,” they lamented. And: “Why are we letting this happen?”

Open since 1946, TBR was the oldest community theater in the city, and one of the oldest in the country. The nucleus of Baton Rouge’s performing arts scene for almost eight decades, its renditions of iconic works like A Christmas Carol and The Rocky Horror Show were annual rituals for many.

The closure news came just six days after a Feb. 24 post about board resignations that followed an allegation about one of its members swirling on social media. TBR declined to discuss the matter with 225, other than to say its investigation was closed.

But the issue, which followed other public and behind-the-scenes controversies, exposed TBR’s organizational struggles. At least four board members resigned earlier this year, as did TBR’s artistic director Sarah Klocke after less than five months on the job. Klocke did not return requests for comment.

Internal strife notwithstanding, the board pinned the closure on funding, pointing to inflation, debt, building and equipment maintenance costs, and a continuing decline in ticket sales.

“We really were struggling from COVID and beyond to kind of regain our footing,” says Andrea Tettleton, who joined TBR’s volunteer board of governors last August and stepped into the board presidency days before the announcement. “We just haven’t been able to locate that financial support in the way that we had hoped.”

Long COVID

Former TBR artistic director Jenny Ballard, now a theater professor in Tennessee, led the organization through the pandemic. She recalls the painful decision she and the then-board of governors made in closing The Fox on the Fairway, set to open in March 2020.

When shows resumed later in 2020, they saw smaller crowds and generally ran over two weekends rather than the usual three, she says. But even with the struggles brought by the pandemic, Ballard expected TBR to pull through.

“It never crossed my mind to close the theater,” she says. “The goal at all times, no matter what, (was) to keep the doors open.”

“It never crossed my mind to close the theater.“

—Former TBR artistic director Jenny Ballard

Following COVID-19, TBR and other theaters nationwide relied on long-term, low-interest loans from the federal government to stay afloat. Such loans plugged income shortfalls temporarily, but they also added debt to balance sheets. Crowds never returned to pre-pandemic levels. Meanwhile, production costs doubled. Building supplies, labor costs and insurance have all spiked.

According to TCG’s Theatre Facts report, released in March and analyzing 2023, theaters are facing not just soft ticket sales, exorbitant expenses and a cessation of federal funding, but also a “worrying” three-year decline in charitable giving among trustees, Schulenburg says.

Patron behavior has also changed. Theatergoers are more likely to buy show-by-show tickets rather than committing to a season. Once TBR’s lifeblood, seasonal subscriptions decreased from 937 to 450 over the last five seasons, after peaking to nearly 6,000 in 1970, according to Tettleton.

“The language that gets used is that ‘it’s like a leaky bucket,’” Schulenburg says. “There are audiences going in, but they’re not returning or converting into subscriber or donor status, a pattern that used to be the norm.”

Theatre Baton Rouge had been open about its post-COVID fiscal challenges in 2023, launching its urgent $100,000 Light the Stage fundraiser. The community stepped up, and the campaign surpassed its goal. While it helped pay down some debt, it wasn’t enough to secure the future, Tettleton says.

A growing number of theaters, Theatre Baton Rouge included, have had to budget for deficits in the post-pandemic era. TBR’s 2023 tax return shows $836,603 in revenue and $993,226 in expenses—a $156,632 budget shortfall. The organization’s reported net assets that tax year were -$300,211. It squares with national trends.

“Theatre Facts 2023 records the worst change in unrestricted net assets, or CUNA, since we’ve been recording that data, not only in the number of theaters experiencing a negative change in their unrestricted net assets, but also the severity of that change,” Schulenburg says.

Casting call

Despite the current climate’s challenges, the local live theater sector has sprouted fresh energy and new programming in recent years. The groups might have a smaller footprint than TBR’s, but their overhead is far lower.

The past decade brought newcomers like women-centric Red Magnolia Theatre Company and 225 Theatre Collective, largely volunteer-run groups offering familiar and experimental productions. The 130-seat, volunteer-operated Sullivan Theater has seen steady increases in ticket sales since it opened in 2013, according to Freneaux. Its spring opener, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, was a complete sellout, including an extra show to meet demand.

“When it comes to community theater, it’s larger than just one place,” says actor Knick Moore, who recently starred as Hercule Poirot in Sullivan’s Murder on the Orient Express. “While TBR was the biggest, there was a lot of participation across other theaters.”

Indeed, Ascension Community Theatre celebrates its 25th anniversary this year. Fields and fellow LSU theater student and Xanadu star Kamryn Hecker recently headlined ACT’s well-received spring production of Cabaret.

There’s been hopeful news for UpStage Theater Company. The small grassroots group has been named the resident company for the recently renovated historic Lincoln Theater, slated to open soon as a performing arts hall and Black history cultural center. The local fabric also includes established players like LSU’s professional theater, Swine Palace.

Still, there’s no denying that TBR was the dramatic arts fulcrum, churning out back-to-back productions with a deep bench of onstage and backstage talent.

Founded by volunteers and then-named Baton Rouge Civic Theater, TBR put on its first shows in a space at Baton Rouge Metro Airport. In 1951, its name changed to Baton Rouge Little Theater—which many native Baton Rougeans still use. The Little Theater rebranded as Theatre Baton Rouge in 2013.

Ballard became its artistic director in 2014, pushing for additional larger-scale and edgier productions. TBR was where many local actors, set designers, directors and backstage crews cut their teeth. Talent was never in short supply. Regional music and theater teachers auditioned for shows, along with LSU School of Theatre students, who’ve long used TBR as a classroom extension, Fields says.

“Being in a local show gives you the chance to apply what you’ve learned in front of an audience,” he says. Some LSU theater alums returned to TBR after working professionally in larger markets, adds LSU School of Theatre Associate Professor Shannon Walsh.

“Some of the shows I have seen at TBR rival shows that I would have seen from when I worked in Minneapolis, which is a huge theater city,” she says.

Next act

TBR’s closure was seen as abrupt because the nonprofit seemed to be conducting business as usual.

This past fall, its play selection committee chose the shows that would have comprised a milestone 80th season. And in February, TBR was selling ticket bundles for all remaining performances, signaling those shows would take place. Even the Feb. 24 announcement about board leadership changes invited community members interested in filling open board positions to reach out.

But behind the scenes, the financial picture was bleak. Facing overdue building and equipment maintenance costs, plus the pressure to purchase the rights to perform and advertise the 80th season shows, Tettleton says a quorum of the remaining eight-member board of governors made the unanimous decision to pack it in.

“We have exhausted every option,” their announcement said.

“I just hope that space doesn’t get bulldozed over or repurposed into something else.”

—LSU School of Theatre Associate Professor Shannon Walsh

While TBR is no more, it’s possible something could become of its space, which Walsh says is an enviable arts asset. A handful of concerned theater experts met with TBR’s board this spring to discuss the future, but as of early May, nothing had been decided.

“We have a growing landscape of theaters, but we are a very space-poor community,” Walsh says. “I just hope that space doesn’t get bulldozed over or repurposed into something else.”

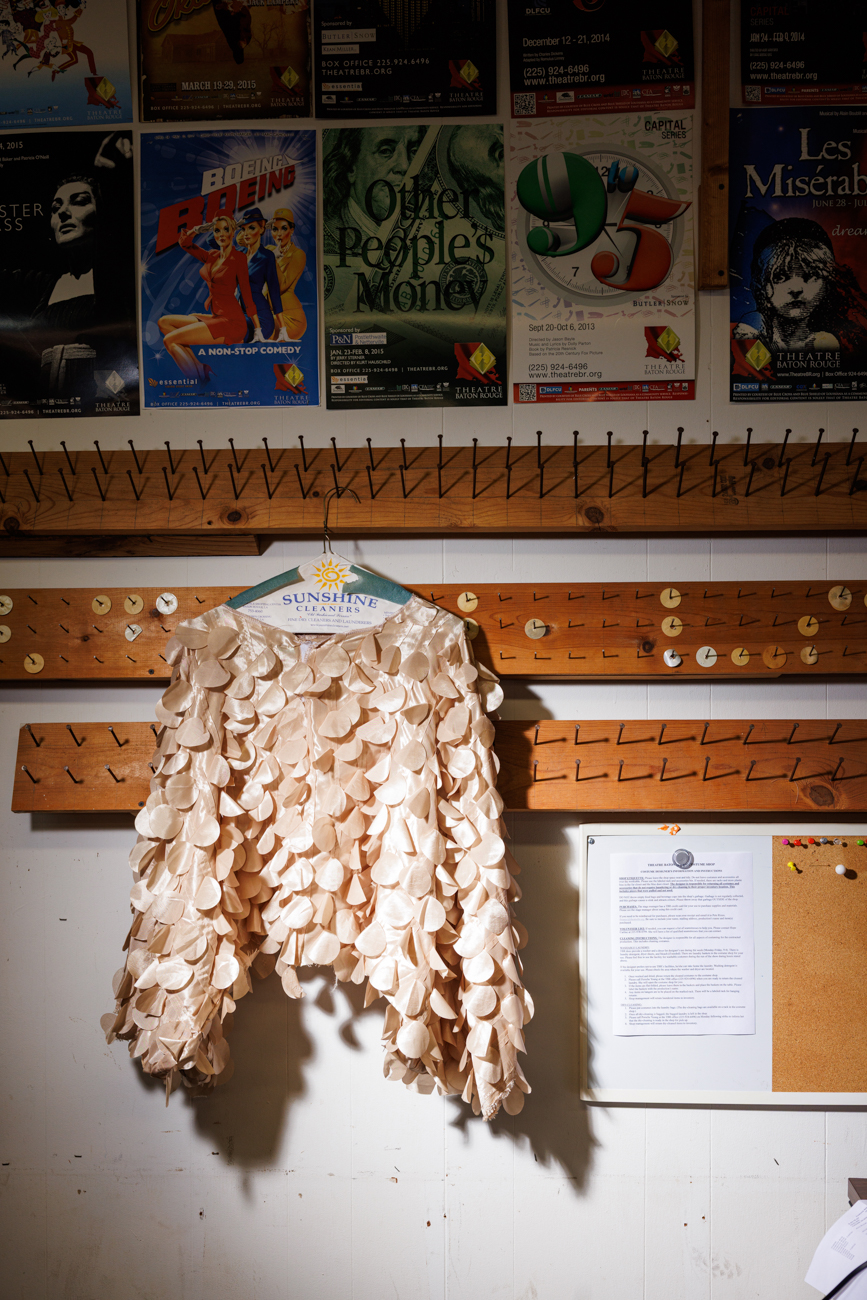

Last month, the building held its final event for now: a costume sale. More than 70 people snagged limited reservation slots, sifting through racks of relics.

TBR’s history can’t help but cast a long shadow over regional dramatic arts. But actors like Moore have a different vantage point.

“We had 11 performers in Murder on the Orient Express and (130) people in the audience for eight shows. So, the theatergoers are there. The theater will continue to be here in one capacity or another.”

The shows must go on

Catch summer productions from these other theaters

Playmakers of Baton Rouge

Seussical, Jr.: June 6-8 and June 13-15

Sullivan Theater

Oklahoma!: June 13-22

Noises Off: Aug. 15-24

UpStage Theatre Company

Mahalia!: June 27-28

The Old Settler: July 18-20

Ascension Community Theatre

Annie: July 10-27

Christian Community Theater

Singin’ in the Rain: July 27-Aug. 3

This article was originally published in the June 2025 issue of 225 Magazine. Portions of it were adapted from a 225 Daily feature that was reported in late March 2025.

|

|

|