Remembering the ‘Woodstock of Louisiana’

In 1969, a music festival drew national acts and 30,000 music lovers to Prairieville

For three days, people camped in tents or cars. The more intrepid ones even slept directly on the grass.

Attendees had come by car, bus, motorcycle and on foot. They stood in a crowd 30,000 deep at a now-defunct speedway, a dirt track measuring about three quarters of a mile.

It was the end of August, and the Louisiana summer heat was unforgiving. The sun beat down on the dedicated masses, who remained planted in front of the stage from 11 a.m. on Aug. 30, 1969, until 2 or 3 the morning after

Sept. 1.

“It was the festival of no sleep,” Baton Rouge native Paul Waguespack says.

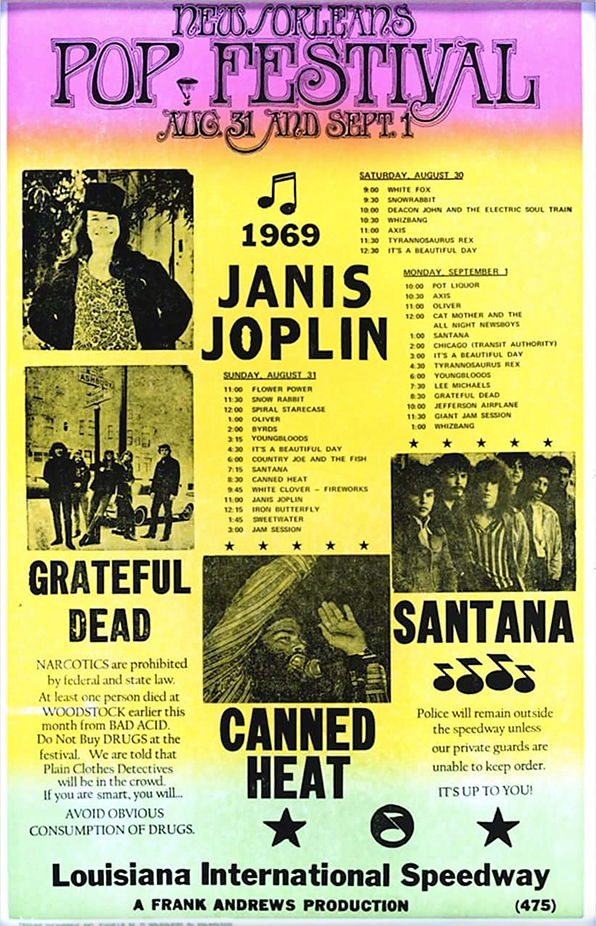

News articles at the time often referred to the festival as Louisiana’s version of the Woodstock Music and Art Fair, though the festival’s real name was the New Orleans Pop Festival. That was a misnomer of sorts; the festival was actually closer to the Capital City than New Orleans, around 15 miles away in Prairieville.

Festival organizers went with the New Orleans name because the Crescent City was more widely recognized than Prairieville and, in their minds, more likely to attract attendees during a year when 18 other music festivals sprouted in fields and stadiums across the country.

The festival took place two weeks after the infamous Woodstock, and several Woodstock performers appeared, including Janis Joplin, Grateful Dead, Sweetwater, Santana, Canned Heat and Jefferson Airplane.

The festival took place two weeks after the infamous Woodstock, and several Woodstock performers appeared, including Janis Joplin, Grateful Dead, Sweetwater, Santana, Canned Heat and Jefferson Airplane.

Although most of these acts are now largely considered to be legendary influences in popular music, little of the festival itself is remembered outside of local accounts. While Woodstock attracted hundreds of thousands of attendees, the New Orleans Pop Festival couldn’t replicate that level of turnout, attracting about 30,000 attendees.

But for a few local avid music fans, the weekend was one they’ll never forget.

Waguespack bought his ticket for $8 from a local record store after hearing about the event on one of the radio stations in town. A graduate of Redemptorist High School, Waguespack was about to begin his freshman year at LSU. During the festival, he and a friend slept in his station wagon in a field near the raceway.

“I had never experienced anything like that,” he says. “It was an eye-opener, for sure. A great deal of fun.”

BK Tomlin, then 19, hitchhiked to the festival from his home in New Roads and used the last of his money to buy a ticket. Tomlin, now 67, would grow up to become a chemist. But that night, he was young and free, sleeping in front of the stage for the duration of the festival, and he wasn’t alone.

“I had no food but didn’t really care; the music was awesome,” Tomlin says. “When it was over, I hitchhiked back to LSU. It was between semesters, so there was no one there. I found an open dorm window and crawled in to get a shower and spend a night on a bed with a mattress. The next morning, I hitchhiked back up to New Roads.”

Tomlin’s most memorable acts included Santana—whom he hadn’t heard of prior to the festival—and Grateful Dead and their awe-inspiring light show.

People flocked from across the country to Prairieville and were collectively dubbed as “the hippies” by local news outlets at the time.

“Despite their claims of individuality, there is a startling sameness about the hippies on hand for the festival, with almost all resplendent in the colorful garb and long hair for which they have become known,” read an Associated Press report published in The Times-Picayune on Sept. 2, 1969.

For one young Baton Rougean, that report might have been just a little nostalgic. Layne Cannon, now 65, started the first day of his senior year at Broadmoor High School a few hours after returning from the festival. The then-17-year-old bought tickets for himself and his 15-year-old brother against his parents’ wishes.

Cannon made a deal with his father, who finally agreed to let him go under one condition. Cannon’s hair was unruly and long, and he would only be allowed to attend the festival if his mother cut his hair upon his return, before he attended school the next day.

Sure enough, in the early hours of Tuesday morning, Cannon’s long “hippie” locks were gone. But he had no regrets.

Of Baton Rouge’s answer to Woodstock, Cannon says, “It was hot, dirty and wonderful.”

This article was originally published in the September 2017 issue of 225 Magazine.