RDA seeks residents’ ideas for a future Plank Road with new developments and a rapid transit line

People of all ages fill the bus in the parking lot of Sacred Heart on a March morning. There is a lively and friendly energy in the air as strangers chat about everything from statement necklaces to state politics.

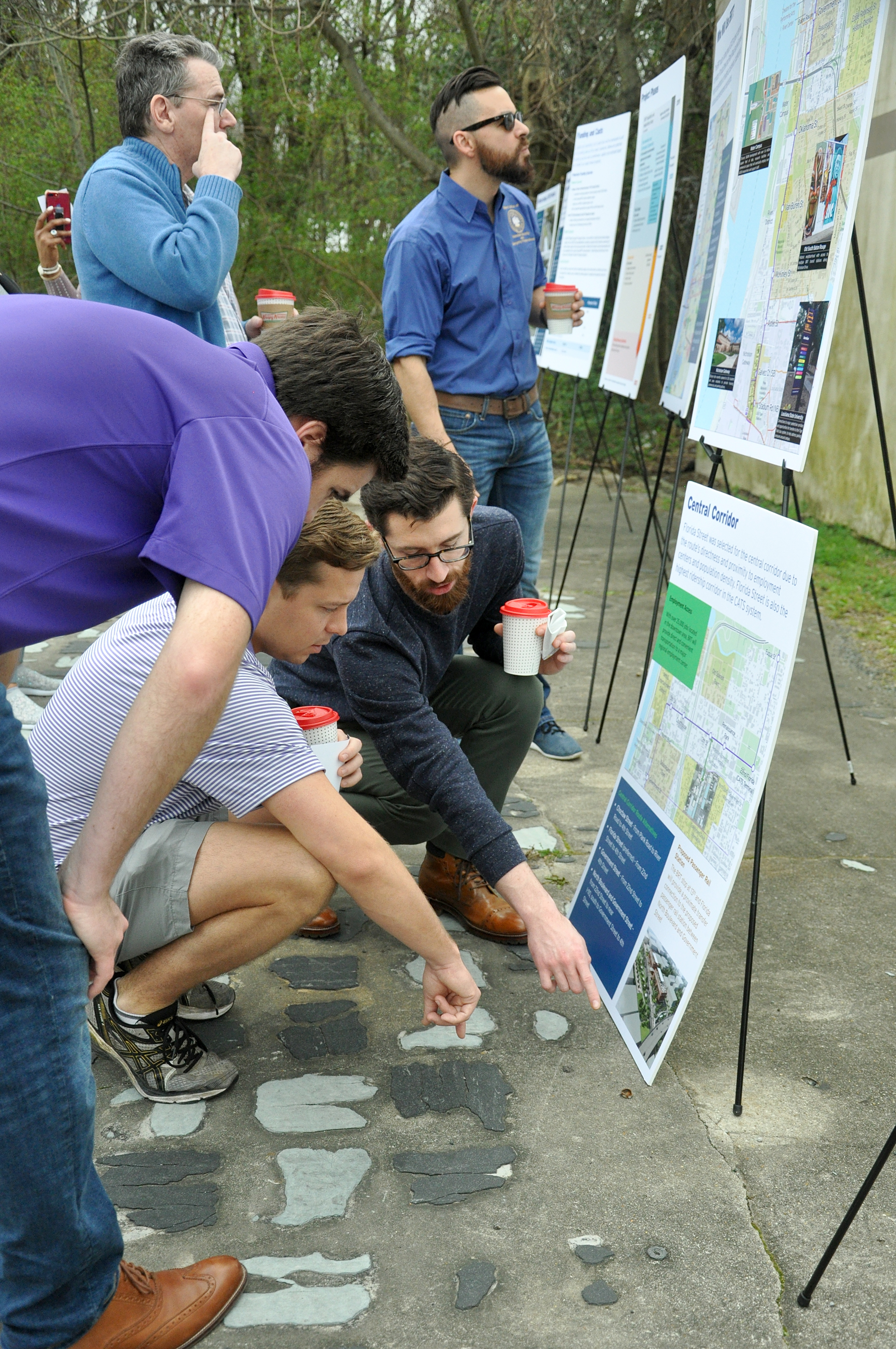

“Walk the Plank,” the day’s tour of a stretch of the city previously overlooked by developers and community leaders, is about to commence. Organized by the East Baton Rouge Redevelopment Authority, the tour has drawn around 40 riders today. Some are residents of the area, some are community leaders, and others are keeping an eye out for possible real estate opportunities. But this morning, all of them share a common goal: envisioning Plank Road’s potential.

The bus tour is just the first of several community engagement initiatives seeking feedback on the plan to revitalize Plank Road under the re-energized RDA. The Louisiana Legislature created the RDA in 2007 to prioritize development in the parish. But in 2014, former Mayor Kip Holden cut funding to the agency, resulting in the layoff of most of its staff.

|

|

Mayor Sharon Weston Broome reinvigorated the RDA when she took office in 2017 by aligning it with the Office of Community Development and the Housing Authority agencies. Since then, the organization has expanded from two employees to around a dozen, says RDA community engagement specialist Geno McLaughlin.

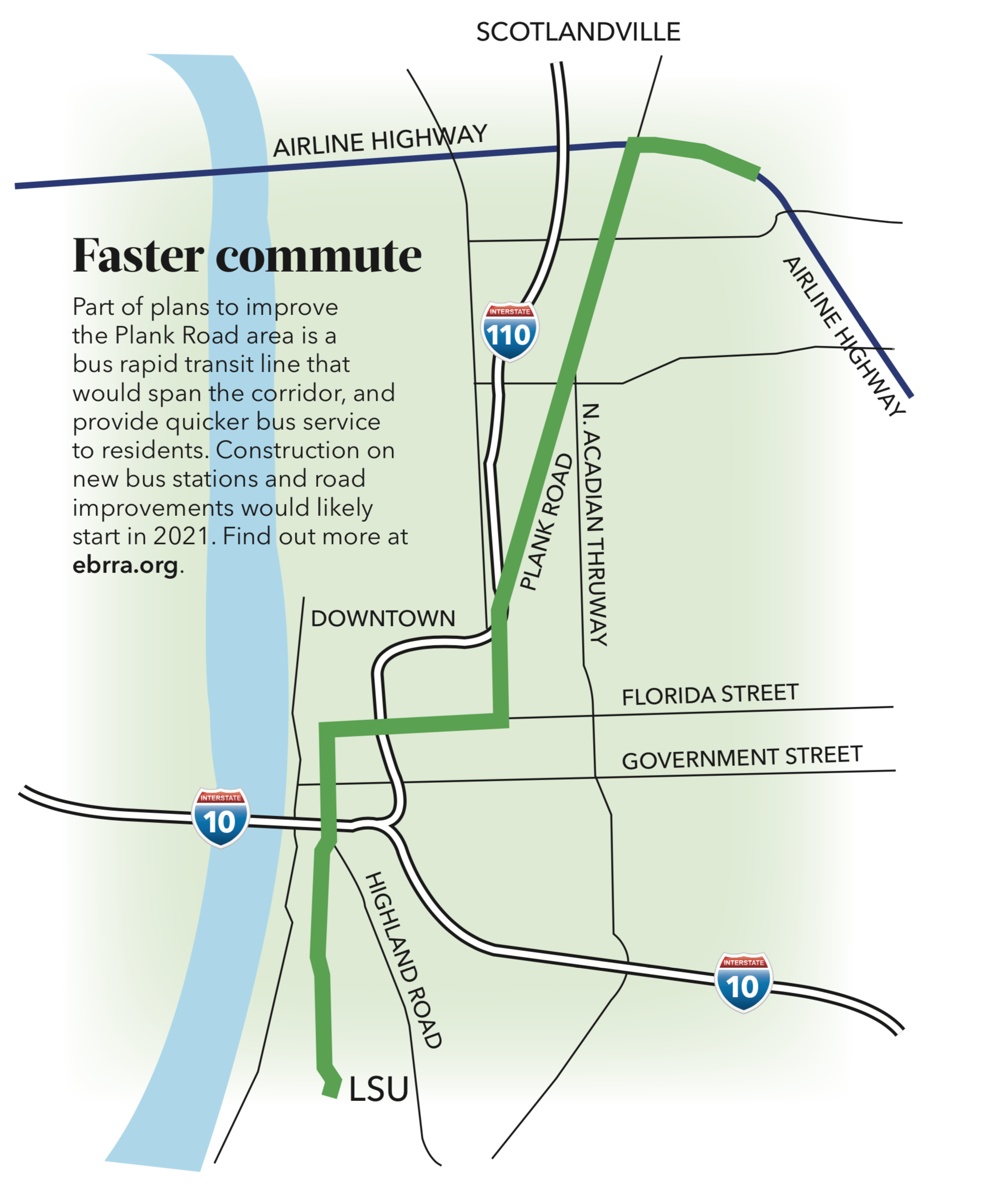

The first stop on the tour is a lot decorated with posters that detail a $50 million plan for a bus rapid transit line along the Plank Road and Florida Street corridors—two areas with high concentrations of no-car households. The route would stretch between Scotlandville and Glen Oaks to LSU, operating on a straight path to maximize speed and efficiency.

Plank Road area resident Ethelyn Blackmore agrees that a more efficient transit system is long overdue. She recalls long bus rides to work as a teenager. The commute took two and a half hours there and another two and a half hours back—all so she could work a four-hour shift.

“These people are important,” Blackmore says. “You think about the working poor—they do jobs that we need.”

The rapid transit project would be a partnership with the Capital Area Transit System and engineering firm HNTB. It would make use of dollars from the state’s Department of Transportation and Development Road Transfer program and potential federal and local sources. Project leaders expect construction for the transit line—on things such as bus stations and improved sidewalks—to begin in 2021 and operations to start in 2023.

Chris Tyson, RDA president and CEO, says while the inclusion of a mass transit system in a redevelopment plan is new to Baton Rouge, it is “par for the course” in other communities around the country. “If we want to aspire to some of these other models, we have to do some quick catch-up work,” he says.

The next stops on the Plank Road tour bring attendees to locations that are prime for redevelopment for business use and affordable housing.

RDA leaders encourage attendees to brainstorm ideas for a gray brick building and vacant lot on the corner of Plank and Weller Avenue, asking them what the community needs. Several adults discuss healthy grocery stores and sit-down restaurants, while children draw pictures of indoor playgrounds serving free lemonade and soft drinks.

Throughout the day, McLaughlin notices a demand for family-friendly businesses, both for child care and educational purposes. “In every community, everybody wants happy and healthy kids and spaces that they can send their kids to and know that they’ll be safe,” he says.

McLaughlin says residents are reacting with curiosity about what the project will entail, excitement for its potential and skepticism about potential negative ramifications, such as gentrification.

“Once it’s decided that a community is valued now, it’s not value for the residents that live there,” McLaughlin says. “It’s really value for the people that are coming in and how they can make a profit.”

“I understand why people are skeptical of agencies like mine,” he adds, “because they have long been used by people to take away from communities. So I think our charge is: How can we use government to actually invest in the community?”

The RDA is working to make sure potential development here is sustainable, using high-quality materials that will last more than a few years. But McLaughlin says community members can also use their “people power” to push back against shoddy development.

“They have the ability to raise awareness and say, ‘Hey, if you’re going to come in, make it equitable,” McLaughlin says. “‘Make it the same type of development that you would put on Perkins Road or on Bluebonnet. Yes, it might cost you a little bit more to do a little brick siding, but it’s the type of thing that will actually add value to the community.’”

The RDA plans to host the Plank Road Street Festival in June, where the organization will display temporary models and art installations to give residents a glimpse of what’s in store for the area.

McLaughlin says with this project and others, he hopes the RDA is starting a conversation about equitable development throughout the parish. “If we’re going to do development on one side of Baton Rouge, we cannot ignore the other side,” he says. “I learned in math what you do to one side of the equation, you must do to the other side. We’re trying to even out the equation here.”

SOURCES: Baton Rouge Business Report and local news reports

This article was originally published in the May 2019 issue of 225 Magazine.

|

|

|