15 big moments and trends that have redefined the Capital Region since 2005

2005

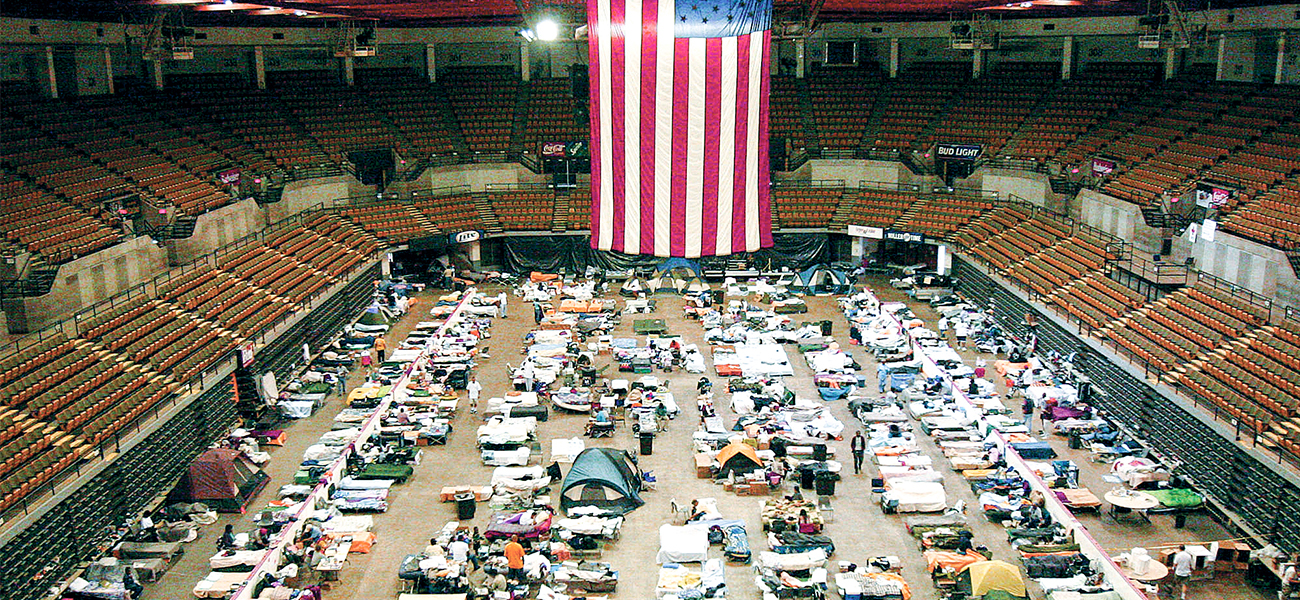

Hurricane Katrina forever changes Louisiana.

Hurricane Katrina upended life unalterably in New Orleans. And after the levees broke and the city filled with floodwaters, Baton Rouge became high ground. Thousands of evacuees relocated here—at least temporarily—while New Orleans rebuilt. Some came by choice, and others arrived because they had nowhere else to go. A FEMA trailer shelter called Renaissance Village was established in Baker, which operated until 2019. Baton Rouge staged the National Guard’s relief efforts, and became the center of operations for evacuated New Orleans businesses and nonprofit agencies. Though it’s difficult to know how many former New Orleans residents moved here permanently, Greater Baton Rouge’s population grew by about 105,000 from 2004 to 2019.

2005-now

Historic elections redefine local politics.

|

|

State and local elections over the last 15 years have been anything but boring. Louisiana’s first woman governor, Kathleen Blanco, was succeeded by the state’s first Indian-American governor, Bobby Jindal, in 2008. In 2004, Baton Rouge saw its first elected African American mayor, when Melvin “Kip” Holden defeated Bobby Simpson and went on to serve three terms. Holden was followed by Sharon Weston Broome in 2016, the city’s first elected woman mayor and second Black mayor.

After Katrina, Baton Rouge rebuilds in its own way

How did New Orleans reshape our city? Here’s an excerpt from a 225 staff editorial from our first issue:

Turns out 2005 was grow-up or shut-up time for Baton Rouge.

Hundreds of thousands of newcomers sought refuge here after Kat-Rita, bringing out the best and worst in the community. Baton Rouge dodged two historic hurricanes, but the city has been challenged.

In a way, the city has been given a gift, a rare chance to evolve into a more cosmopolitan place. Will it become a place that absorbs new ideas or just get better at bouncing them out?

For much of its history Baton Rouge has been a place where “big city” meant something bad. Now, in more ways than anyone was prepared for, Baton Rouge has become a big city.

It has required us to adapt in order to maintain our quality of life.

We have to be more patient on the roads, we have to accept strangers in our spaces, and most important, consider new points of view.

New Orleans has no choice but to rebuild and re-invent itself. In a way, Baton Rouge has the luxury of doing the same. Let’s not blow the chance.

2008

Hurricane Gustav blows through Baton Rouge.

The second-most powerful storm of that year’s hurricane season, Gustav made landfall in Cocodrie on Sept. 1, causing damage in 34 Louisiana parishes, including East Baton Rouge. Winds ripped through neighborhoods like Old Goodwood, knocking down old hardwoods like matchsticks. For days, nearly a million state residents were without power, including 300,000 in Baton Rouge.

2011-now

On the path to becoming a “complete” street, Government Street fuels Mid City’s growth.

The late John Fregonese, an innovative planner from Portland, Oregon, led the East Baton Rouge Parish Comprehensive Master Plan in 2011 and was a champion of Government Street. Fregonese teased out a vision for the corridor that included reimagining an abandoned Entergy substation at Government and 16th Street (now the Electric Depot) into a mixed-use facility, and transforming Government Street from a speedy thoroughfare into a complete streets asset. Nearly a decade later, much of the vision set forth in the FuturEBR Master Plan has been realized, with a significant portion of Government Street now outfitted with bike lanes and traffic calming measures. Lots of private investment has taken place up and down the street, including ventures like Curbside, Tim’s Garage, French Truck Coffee, Ritter Mayer Architects, Mid City Beer Garden, the Radio Bar, Elsie’s Plate and Pie, Rocca Pizzeria and more.

October 2018: “When I first got to Mid City, it felt like I was beating a drum and no one was listening. Today, they’re beating with us, and we’re making some pretty good music.” —Samuel Sanders, Mid City Redevelopment Alliance’s executive director since 2006, recalling his early efforts to promote the area

2012-now

St. George divides the community—literally and figuratively.

In 2012, residents in the southeast part of the parish frustrated by the poor performing East Baton Rouge Parish School System proposed to the Louisiana Legislature that they form their own school district. Eight years later, the fight continues, with twists and turns no one could have predicted. Organizers needed a two-thirds majority of voters in the area to move forward with a school district, and attempts to get the votes failed twice. Then, organizers changed strategies, proposing to voters that they form their own city and keep tax dollars close at home for not only schools but drainage and traffic, too. Voters agreed, giving the green light to form the new city of St. George in 2019. A month later, Mayor Sharon Weston Broome and others sued, sending the thorny issue, for now, to the courts.

April 2014: “It’s very stressful to think about. [Children’s] educational fate is in part dependent on defeating this breakaway school district. I just couldn’t sit by and let it happen without trying to stop it.” —Belinda Davis of One Community One School District

2013-now

New bike trails improve quality of life.

Councilman Buddy Amoroso’s 2018 death while cycling in West Baton Rouge Parish was not the first biking fatality in the area. But coupled with numerous fatalities over the years, it was another reminder of the Capital City’s serious need for safer cycling conditions. While we still have miles to go (literally), we’ve made significant progress, beginning around 2013 with projects like BREC’s Capital Area Pathways Project, and later, the Mississippi River Levee Bike Path and the Downtown Greenway. In 2019, the long-awaited Gotcha e-bike rentals became available at LSU, Southern, City Park and downtown. They have become wildly popular, with daily rides spiking to nearly 600 this spring.

2013-now

Hospitals open and close, and a health district emerges.

We’ve seen significant changes in health care in Baton Rouge, from the 2013 closure of Earl K. Long Medical Center and the 2015 shuttering of Baton Rouge General’s Mid City Emergency Room (and its recent reopening along with its dedicated COVID-19 wing). Pennington Biomedical Research Center has continued to ascend as one of the world’s premier research facilities linking diet to disease. It—and other projects like the new Our Lady of the Lake Children’s Hospital— are part of the Baton Rouge Health District, established by Baton Rouge Area Foundation in hopes of taking our region to the national stage of health care.

2015-now

Downtown becomes residential.

The opening of Matherne’s Market on Third Street was a critical milestone in downtown’s decades-long revitalization effort. A full-service grocery store, combined with new residential developments, finally meant that downtown had begun to attract a critical mass of permanent, year-round residents. Girded by historic neighborhoods Spanish Town and Beauregard Town, downtown is now home to hip complexes like 440 on Third, The Heron, the Commerce Building, the Fuqua Building, Maritime One and the Kress Condominiums—many of them historic buildings outfitted with sleek renovations. In recent years, the neighborhood has seen a 70% increase in housing units built, with an additional 2,000+ residences in the pipeline, according to the Downtown Development District.

June 2018: “We need to envision a downtown circa 2012 or 2015 that encompasses the current area, Spanish Town, Beauregard Town, the Old South area around the I-10 and the area from east of the I-110 to 22nd Street. Within these boundaries, you can envision 5,000 residents, sustainable retail stores and public transporation.” —Cyntreniks co-owner John Schneider

2015-now

Changes to film tax incentives see Hollywood South fading.

Back in 2002, Louisiana rolled out the country’s most generous tax credit program for film production, quickly dubbing it Hollywood South. Baton Rouge saw a lot of movie-making action—remember when Dukes of Hazzard was filmed around town in 2005? Plenty of other productions followed, from Pitch Perfect to All the King’s Men, thanks also to the formation of Celtic Studios. Ten years later, legislative changes to Louisiana’s tax credit program created uncertainty for filmmakers, cooling their enthusiasm for shooting here. The program saw improved changes in 2017, slowly reinvigorating the sector—until COVID-19 put the brakes on production earlier this year.

2016

Alton Sterling’s killing and the shootings of police officers rock the city.

—Triple S Food Mart owner Abdullah Muflahi, nearly one year after Sterling was killed in front of his store. Photo by Miriam Buckner.

As the July heat descended on Baton Rouge, Alton Sterling, a 37-year-old Black man, was shot at close range by two white police officers during an arrest attempt outside a convenience store. Subsequent protests over the Sterling shooting and policing took place in Baton Rouge. Nearly two weeks later, a Kansas City, Missouri, resident named Gavin Eugene Long shot six Baton Rouge police officers, killing three and seriously wounding one.

2016

Devastating floods shake the Capital Region.

Betsy, Camille, Audrey, Katrina, Rita … named storms are part of Louisiana’s collective memory and storytelling predilection. But it was an unnamed weather system that we’ll be talking about for generations. Relentless precipitation poured into already swollen river systems, causing catastrophic flooding in greater Baton Rouge and beyond. If you were lucky enough to escape flood damage, you could still name scores of others who didn’t. About 150,000 properties were flooded, and one estimate placed the economic fallout for the region at $10 billion.

90%: Initial estimate for the homes that flooded in Denham Springs during the August 2016 flood

I went through this 11 years ago with Katrina, so I knew what to do. I helped my neighbors, walking through chest-deep water. I’ve been doing all I can like Superwoman.

Antoinette Brown, who spent every day after the flood volunteering at her church, Healing Place’s Baton Rouge Dream Center, October 2016

2017

Death of Max Gruver makes national news.

The LSU community was gutted when Max Gruver, an LSU freshman and a pledge at Phi Delta Theta fraternity, died from alcohol poisoning attributed to hazing. The incident was one of several fraternity hazing deaths that year, bringing renewed attention to the issue nationwide. LSU banned Phi Delta Theta from campus until 2033, and in 2018, Gov. John Bel Edwards signed the Max Gruver Act with Gruver’s family standing behind him. The new law stiffens penalties for hazing and requires uniform hazing policies across Louisiana colleges and universities. From their home in Atlanta, Max Gruver’s family launched the Max Gruver Foundation to spread awareness about fraternity hazing. Four fraternity members were indicted on charges of negligent homicide in Gruver’s death, and one, a former LSU student, was convicted in 2019 and sentenced to five years in prison.

2018-now

With new parades on the rise, Baton Rouge becomes more of a serious Mardi Gras town.

You’ve probably experienced the charming, nighttime Southdowns parade or the notoriously raucous Spanish Town Parade—and maybe even the all-female Krewe of Artemis parade, the Mystic Krewe of Mutts dog parade, the Krewe of Mystique parade or the Krewe of Orion parade. But recent years have seen a few more festive events added to the annual Carnival calendar. Mid City Gras formed in 2018, and the Krewe of Oshun Parade and Festival launched this year in Scotlandville. Recent years have seen parades and krewes working to make Mardi Gras a more inclusive and environmentally friendly experience. We have a constantly growing king cake culture, too. Eat your way through dozens of varieties—you’ll even find fresh savory spins, or health-conscious gluten- or sugar-free options.

2020

The community adapts to a COVID-19 world.

Grocery stores without toilet paper. Kids without classrooms. LSU games without tailgating. Celebrations largely canceled. Unemployment on the rise. Life around Baton Rouge has been shaken this year by the spread of the novel coronavirus. In late March, Gov. John Bel Edwards issued a stay-at-home order to curb the spread, shuttering schools and offices, and limiting restaurants to to-go orders. Phase Two openings in May and Phase Three openings in September brought life closer to normal in the Capital City, but we have a long way to go before our regular rhythm is restored. By early October, more than 15,000 people in Baton Rouge had become infected with the coronavirus, and more than 440 had died.

May 2020: In the kitchen, you can go through a multitude of emotions all in a two-hour period. You’re anxious, you’re nervous, you’re frustrated, you’re overwhelmed. But at the end of service, you’re elated. You got your butt kicked, but you made it. And right now, that’s everything we’re feeling, and more. Asking ourselves if we’re going to be able to stay open, the emotions of letting staff go, and then hearing people say, ‘Thank you guys for staying open.’ —Vu “Phat” Le, co-owner of Chow Yum Phat, when asked why he decided to stay open for takeout during the shutdown

2020

Protests and anti-racism advocates push for real change.

The killing of George Floyd by a Minnesota policeman, followed by other deaths at the hands of police nationwide, sparked numerous protests against racism in Baton Rouge. High school students organized a march at the state capitol. LSU football players boycotted practice to march through campus. There were multiple nights of protests on Siegen Lane. And it seemed community leaders were listening. LSU removed from its library the name of Troy H. Middleton, the former university president who wrote a letter in 1961 to the University of Texas chancellor that laid bare his racist beliefs. Lee High School’s name was changed to Liberty High. The debates leading to the name change also saw East Baton Rouge Parish School Board member Connie Bernard instructing people they should learn more about Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. The comments, along with a video that showed Bernard shopping online during the debates, triggered a recall movement to remove her from office that still continues.

This article was originally published in the November 2020 issue of 225 Magazine.

|

|

|