A look at the fascinating histories hidden in Baton Rouge’s oldest cemeteries

There is something equal parts spooky and beautiful about Louisiana cemeteries. The gnarled oak trees draped in moss, the rows of unique above-ground tombs, the weathered statues and monuments. Here in Baton Rouge, the setting has conjured up many a ghost story. But it’s also a treasure trove of tales from the past—not just for local families, but for the Capital City’s place in American history and the battles our ancestors fought.

So as you prepare for a month of Halloween festivities, take some time to appreciate our historic resting places—not just for their creepy vibes, but for their connection to the city’s origins.

Highland Cemetery

The city’s oldest existing cemetery is also one of the easiest to overlook. On the southern edge of LSU’s campus, it’s wedged between townhomes and duplexes off East Parker Boulevard and set off by a wrought-iron fence. The first burial here took place in 1813, and with familiar last names like Kleinpeter, Slaughter and Babin, it’s home to some of the first families of Baton Rouge. It’s also where many soldiers who fought in the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 were laid to rest.

St. Joseph’s Catholic Cemetery

Opened in 1826 on Main Street—in an area that was once the edge of the town proper—this cemetery was available to any Catholics in the area. Many of its inscriptions are in French, and it is home to burial sites of Union and Confederate soldiers. The church also allowed Black Catholic families to be buried there, which was rare at the time. It includes a plot for the Dudley Turnbull family, which was a free family of color in the 1850s.

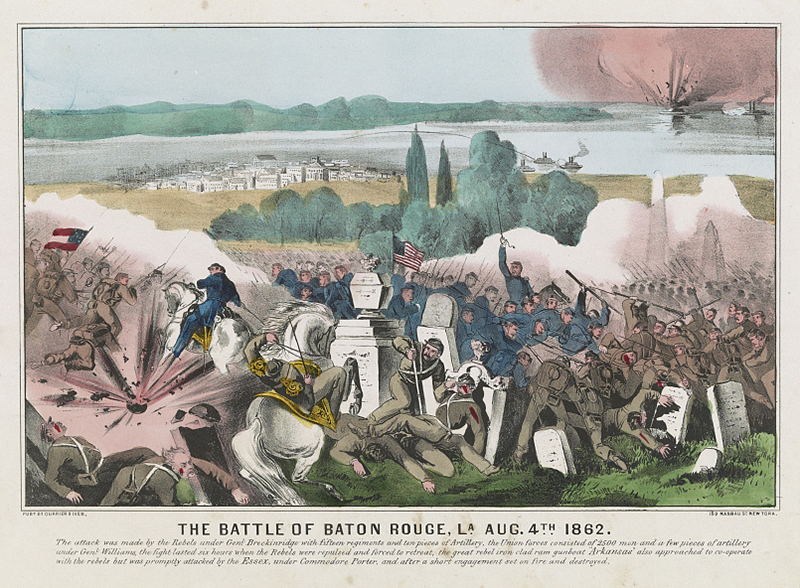

Magnolia Cemetery

About a decade after this cemetery was established on 19th Street, it served as the backdrop for combat in the 1862 Battle of Baton Rouge. Union and Confederate soldiers used its tombs, trees and fences for cover during the battle, which ended in a Union victory at the riverfront. Many Confederate soldiers are buried at Magnolia, while the Union soldiers were moved to the southern portion of the cemetery, which was eventually bordered by Florida Street and became the Baton Rouge National Cemetery after the Civil War. Magnolia was created for mostly white families, though some prominent Black families are buried there. It’s also home to mass graves from the yellow fever epidemic of the late 1800s.

Baton Rouge National Cemetery

Established in 1867 with an entrance on 19th Street, its first residents were those Union soldiers who died in the Battle of Baton Rouge. Other Union soldiers were reinterred here after the Civil War. It’s home to a large commemorative obelisk the Massachusetts state government erected in 1909 to honor Massachusetts soldiers who fought in the Gulf during the Civil War. In the center of the cemetery, the perfect rows of gravestones are broken by a concrete platform where an iron gazebo-like structure once stood for band performances and speeches. There are more than 5,000 service members and their families buried here.

Jewish Cemetery

Many prominent Jewish families connected to the origins of B’Nai Israel are buried in this cemetery on North Street, which was established in 1868. Its first burials were due to yellow fever.

Lutheran Cemetery

On the edge of City Park and Eddie Robinson Sr. Drive, this mostly Black cemetery was established in the 1850s. The hilly property is home to enslaved people from area plantations. Many of the graves were painted in bright colors to honor African and Caribbean heritage.

Roselawn Memorial Park

Baton Rouge entered a new future of burial culture with the establishment of Roselawn in 1921 on North Street. The landscaped garden design was an attractive alternative to the city’s older cemeteries, and a full staff of groundskeepers meant families didn’t have to maintain the areas around graves. Many families relocated their loved ones from the older cemeteries to Roselawn. Several early priests and sisters of St. Joseph Catholic Church were also reburied here in an area designated for Catholics. A. Hays Town designed the manager’s office, which was built in 1954.

Sweet Olive Cemetery

The oldest Black cemetery in Baton Rouge was established on 22nd Street around 1850. It contains the graves of enslaved people from nearby plantations, free people of color, veterans of World War I and II, many civil rights leaders and Black business leaders. Some graves feature folk art carvings and handmade inscriptions; others were covered in mosaic tiles. While much of the cemetery is deteriorating or overgrown, there have been attempts in recent years to clean it up and certify its historic status through a New Orleans-based historic preservation consultant. Preserve Louisiana has previously advocated for Sweet Olive to be put under the care of BREC, which currently maintains Magnolia Cemetery.

Key term

Potter’s Field

Areas of cemeteries reserved for burials of the poor or unknown. Examples of these can be found at Magnolia and Sweet Olive cemeteries.

This article was originally published in the October 2021 issue of 225 magazine.

|

|

|