Bluebonnet Swamp Nature Center is a chance to become one with nature

The corn snake is watching me.

It opens its mouth as I peer into its habitat inside BREC’s Bluebonnet Swamp Nature Center. Its long, orange-brown patterned body is still, but its eyes follow me as I move. We stare calmly at each other, both comforted by the window that safely separates us.

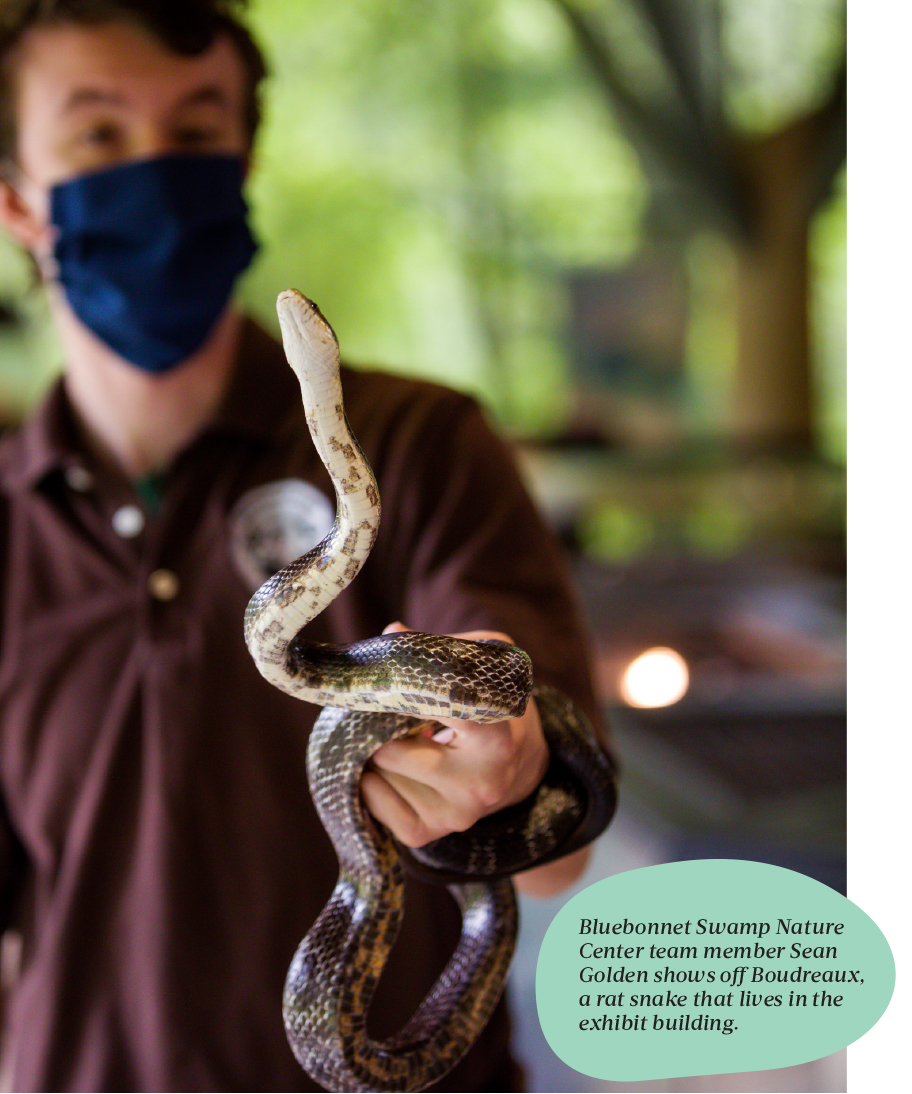

This is one of the more than 20 snakes housed inside the nature center’s exhibit building. One snake sticks its tongue out at me as I watch it. Some stoically slither their wavy, textured bodies across their enclosures as I walk by. Others blend into their environments so well, I can’t even find their camouflaged bodies.

|

|

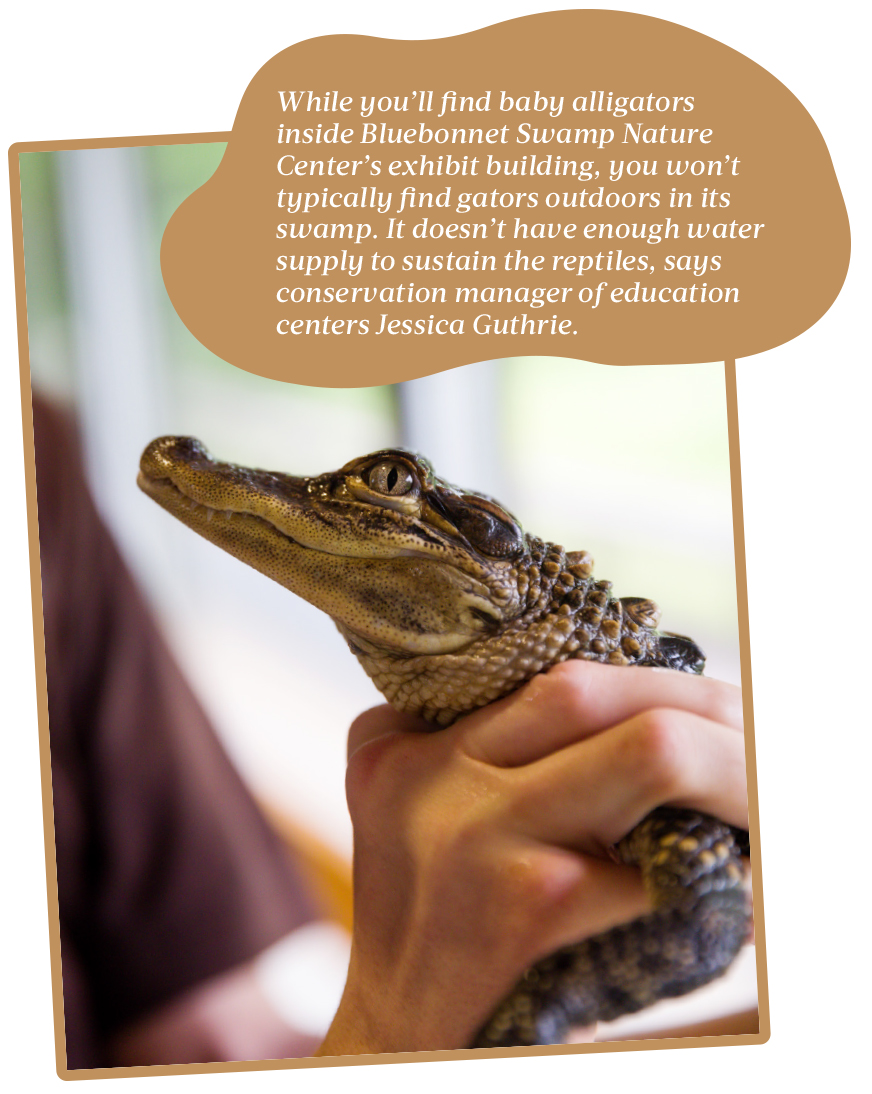

The 9,500-square-foot exhibit building is home to live animals ranging from snakes to salamanders. Turtles sun themselves in window-facing aquariums. In the largest habitat, baby alligators float unblinkingly in the rippling water, their heads about the size of my palm.

During camps and educational programs, kids and families can learn about and even touch some of the center’s creatures.

While the welcome center does house some venomous snakes, most of its 20-plus species are nonvenomous. Printed displays and knowledgeable staff help visitors learn how to tell the difference between the two.

And that is the best part of the job, says Jessica Guthrie, conservation manager of education centers.

“It’s the interactions with patrons, especially young children with a fear of snakes. We get to educate them and change the perspective about an animal everybody thinks is awful.”

Most snakes are harmless to humans, and they play an important role in the ecosystem since they prey on rodents and pests. Besides, as Guthrie reminds visitors:

“Anything that wants to live out there, gets to. It’s their home you’re visiting.”

Guthrie is referring both to the Louisiana wildlife we all coexist with in our neighborhoods, and more specifically, the Bluebonnet Swamp Nature Center itself. The sprawling, 103-acre conservation area includes a cypress-tupelo swamp and beech-magnolia and hardwood forests. It’s home to lizards, ducks, rabbits, opossums, armadillos, otters, and even foxes, coyotes and deer. There are lots of interesting bugs and critters, like the lubber grasshopper, a large black-and-red striped species that might seem scary at first. It, too, is harmless, Guthrie says.

The swamp is tucked just off Bluebonnet Boulevard, surrounded by development on all sides. It’s a convenient location for those who want to walk its boardwalks. But it’s not always a mutually beneficial relationship for the creatures who live there.

“Because we are surrounded by neighborhoods, everything they do, everything they send down the drain, is slowly filling in the swamp and changing it over time,” Guthrie says.

She encourages residents to be mindful of the chemicals they use to wash their cars or the pesticides they use on their lawns.

Nothing might be quite so indicative of humans’ impact on the swamp as how the animals behaved during last spring’s stay-at-home order. With less traffic on the roads and little action at the nature center, bobcats weren’t afraid to walk up to the doors of the exhibit building for the first time.

The swamp’s conservation is in all our hands, and Guthrie encourages us to respect it the same way it nurtures us. She thinks of the children who gleefully spot a new caterpillar on the boardwalk. The birders who arrive in the early hours in hopes of spotting some of the hundreds of species who live there.

Those who visit the swamp as a spectator—not as a disruptor—will appreciate its beauty most.

“Be a part of it,” Guthrie says. “A lot of visitors just keep walking the boardwalk. But if you have time, and a little bit of luck, you can sit and let nature be nature.”

Perhaps no one knows that better than John Hartgerink, a longtime volunteer I run into on my visit. A retired ExxonMobil employee turned self-taught-photographer, he’s captured thousands of photos for the center since he began volunteering in 2002. This afternoon, he’s wearing a beige hat, vest and boots. His camera is slung over his shoulder. He’s spent the morning capturing photos of Barbara and Barry, two owls that Guthrie insists like to show off for Hartgerink’s camera.

As I bid Hartgerink and Guthrie goodbye, I take my own turn at walking the trails. It’s a quiet April afternoon, and for about 30 minutes I seem to be the only human presence left in the swamp.

The sole sounds are the rustling of leaves and creatures calling out in languages I don’t understand. I spot scraggly looking spiders dangling off the boardwalk. I watch the trees sway gently in the breeze, so tall they seem to stretch straight into the sun. I even spot the owl habitat Hartgerink has just photographed. A red and black caterpillar somehow finds its way onto me, crawling up my arm.

But as I exit the swamp, I’m thinking more about all I didn’t see. I wonder how many animals were lurking past my line of sight, just as fascinated by all of us visitors as we are by them. brec.org

This article was originally published in the June 2021 issue of 225 magazine.

|

|

|