A look at some big ideas around the Capital Region that never panned out

THE DOME IS DONE

It was a Baton Rouge attraction even though it lay abandoned. The geodesic dome on Scenic Highway was built in 1958 as a railway tank car service shop. But years of wear and tear and a caving roof led to rumors that it would be demolished for safety reasons. And though the Foundation for Historical Louisiana tried to push for its preservation and renovation, it came down around Thanksgiving 2007.

FILM INDUSTRY ATTEMPTS TO JUMP THE RIVER

|

|

As the state watched its film industry clout grow, plans were announced around 2007 for the nearly $500 million Studio City Louisiana in West Baton Rouge. The massive project on 135 acres of riverfront would include eight sound stages and generate more than 5,000 permanent jobs. It was expected to be operational by 2009 with the help of Gulf Opportunity Zone bonds. But by 2008, little traction had been made, and the project got tied up in legal disputes.

IT’S DEFINITELY NOT ALIVE!

Mayor Kip Holden’s ambitious plan for a riverfront tourism attraction needed major funding for its $248 million price tag. The plans for Audubon Alive, a nature-themed park with an aquarium and 4D theater, went before voters as part of a $1 billion bond. It failed in November 2008, and the idea never came up again. Its location just south of Hollywood Casino has since been floated as a passive park, with boardwalks that can withstand the rise and fall of the river.

FLICKS DOWNTOWN?

As the city worked to develop a designated arts and entertainment district downtown, talk brewed of the need for a movie theater. Early plans to renovate the Kress Building included mockups of an art-house

cinema. But when the building opened in October 2008, that wasn’t part of the amenities. Still, the Manship Theatre has filled the gap over the years, hosting film festivals and movie screenings.

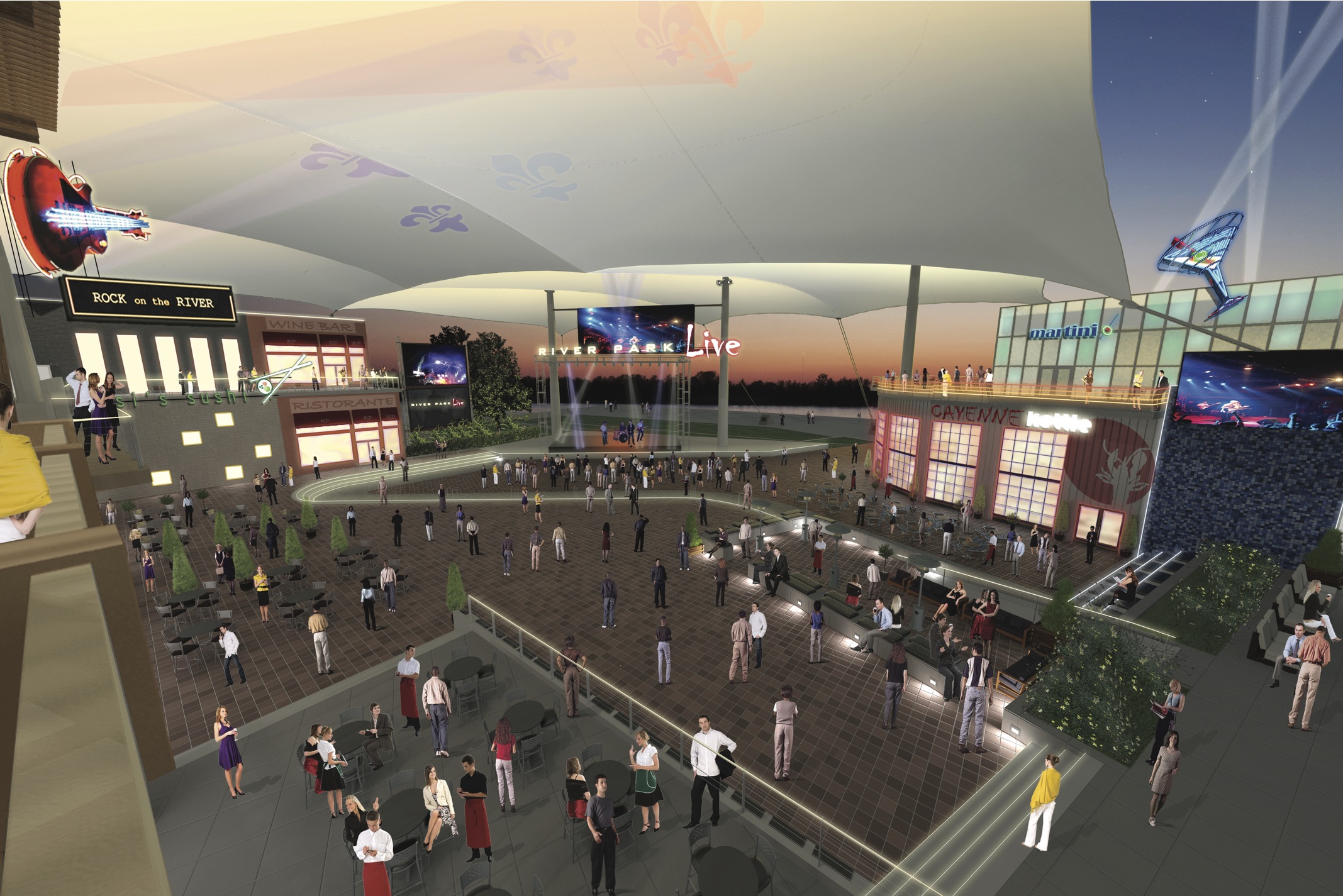

A RIVERFRONT PERKINS ROWE

Developer Pete Clements had a $600 million idea for a mixed-use development just north of Hollywood Casino that would include an open-air concert venue, several multi-story residential and office buildings, restaurants, shops and a hotel. Things seemed to be moving forward for River Park: Clements partnered with the casino to build a railroad underpass from River Road, and the state legislature approved a special tax financing district in 2010 to help with funding. But by 2016, little movement had been made, and the banks threatened seizure of the 36.8-acre property over ongoing financial disputes.

THE PUSH FOR A REVITALIZED LINCOLN THEATER

The Louisiana Black History Hall of Fame purchased the rundown space in Old South Baton Rouge in 2009 and soon began repair work. Its important history as a Black movie theater and the site of organizing efforts for the Baton Rouge Bus Boycott of the 1950s make it a vital hub for revitalizing the neighborhood. The overhaul would create a performing arts and exhibition space with a $4.9 million price tag (at the time, at least). And while restoration efforts have seen starts and stops in the years since, this is one project that might still have a future thanks to the passionate efforts of preservationists.

A CONTROVERSIAL DOWNTOWN LIBRARY PLAN

Trey Trahan, the architect of eye-catching structures like the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame, was a frontrunner to design the new River Branch library downtown in 2011. But a side-by-side comparison of his ambitious design and a similar proposed library by a different developer in the Czech Republic circulated among the selection board. Trahan was soon passed over amid allegations of plagiarism. Frustrated by what he saw as an attempt to tarnish his credibility, he relocated his firm to New Orleans. (And, the troubles for the downtown library didn’t stop there.) But Trahan hasn’t completely abandoned Baton Rouge; he’s since designed the Crest stage downtown and the Magnolia Mound visitors center. Yet the prolific designer’s plan for a mixed-use structure on the old City Dock was scrapped for the Water Institute for the Gulf, and his design of a slim, 26-story residential tower wedged between the Shaw Center and River Road has yet to gain traction.

THE STREETCAR SOME OF US DESIRED

The project seemed like a no-brainer at the time: A public transit line linking downtown to LSU along Nicholson Drive. What form it would take was a matter of contention as the city secured federal funding in 2015. Some people wanted a New Orleans-style streetcar, others wanted a modern tram line that blended in with the futuristic Water Campus just breaking ground on Nicholson. Though the sleek tram line model won out and the Metro Council threw $10 million at the project in 2018, Mayor Sharon Weston Broome scrapped plans in favor of a 9-mile bus rapid transit line connecting Plank Road to LSU. The new project likely wouldn’t

begin service until 2023.

This article was originally published in the November 2020 issue of 225 Magazine.

|

|

|