Open 87 years in Valley Park, Owens Grocery & Market named 2025 Soul Food Pioneer

For Cynthia Owens Green, the commute to work is short and hasn’t changed in years. The 75-year-old wakes up before 4 a.m. and walks from her house across Balis Drive to Owens Grocery Market & Deli. Inside the modest storefront, she and a small team will serve a scratch-made country breakfast, followed by a changing daily menu of Southern plate lunches.

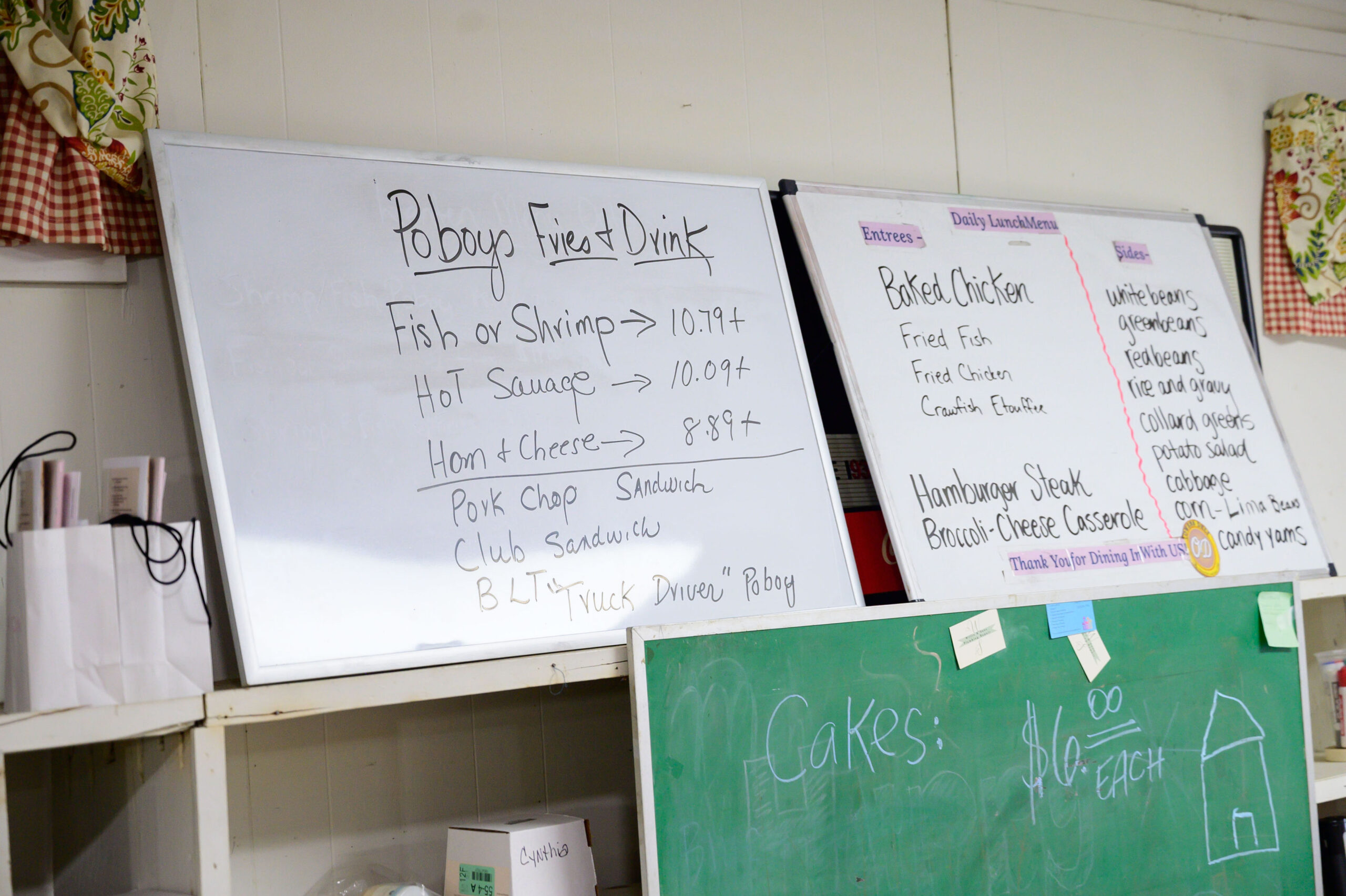

Many of her customers grew up here in Valley Park, or live or work nearby. Some call in orders after glancing at the day’s offerings on Facebook, but others prefer to queue in the hot food line for a visual on the rotating bounty. Through the glass shield, they spot aluminum pans heavy with dishes from the soul food canon. Some days, it’s fried fish and fried chicken. Other days, it’s baked turkey wings, hamburger steak, smothered pork chops and lasagna. A stash of braised, scallion-topped pigtails lurks in the back for die-hards. Requisite red beans and rice—a constant in Louisiana’s soul food-verse—appears daily.

This weekend, Green will be named the Baton Rouge Soul Food Festival‘s annual Soul Food Pioneer, an award bestowed on one local eatery known to embody soul food traditions. The festival takes place May 17-18 at the Main Library at Goodwood and features live music, food and arts and crafts vendors, and a soul food cooking contest. Past Soul Food Pioneer honorees include Chicken Shack, D’s Soul Food Café, The New Ethel’s Snack Shack and Café Express.

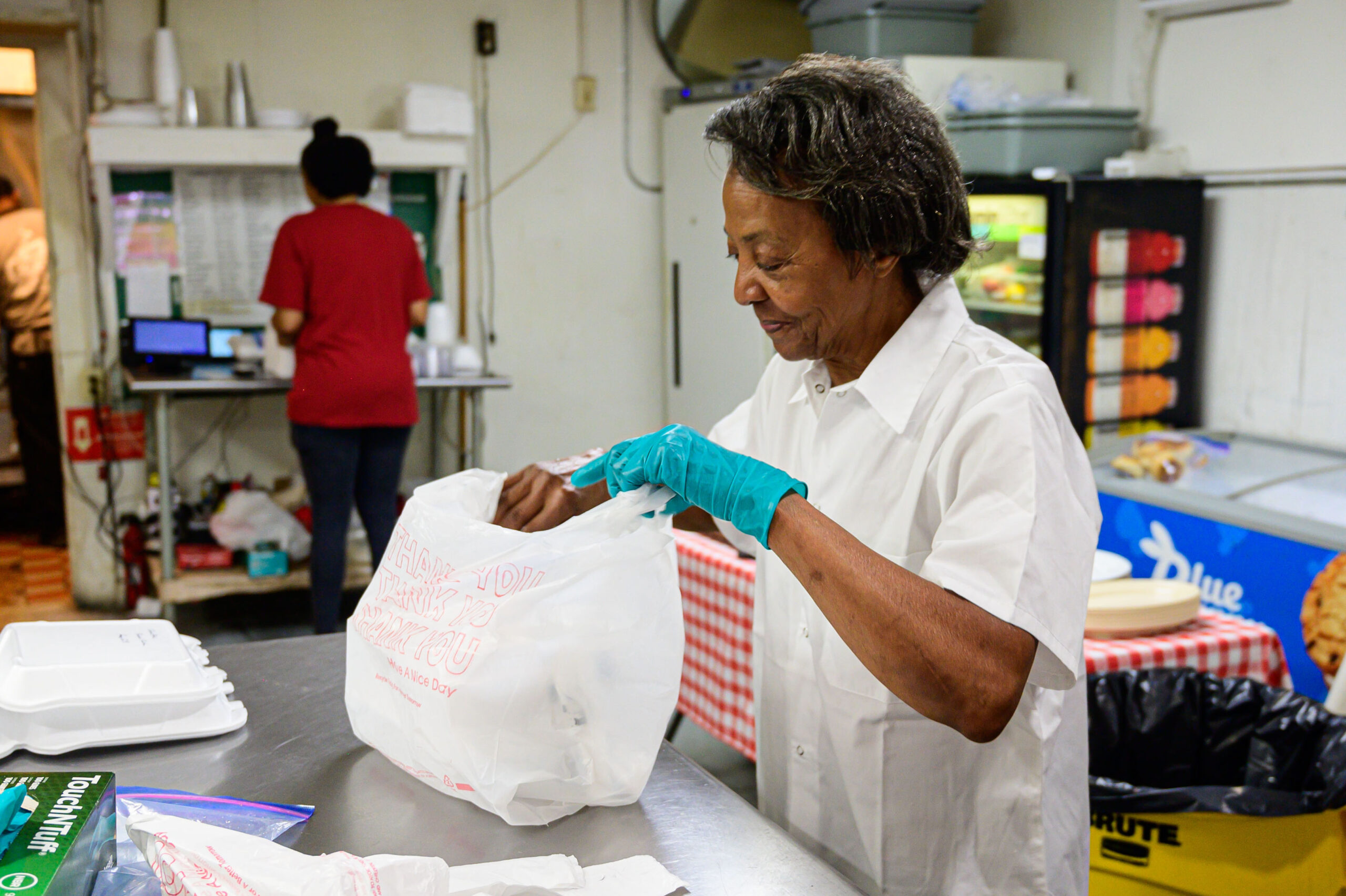

By lunchtime, Green has been cooking for hours but radiates genuine warmth and calm. She greets customers with a soothing, “You okay?” She asks regulars about their families and makes newbies feel at home.

“I never forget a face,” she says.

Green’s parents, David and Emma Owens, founded Owens Grocery & Market after David retired from the mail room at Standard Oil in the late 1930s. It operated first as a filling station and hardware store, but later sold hot meals prepared by Miss Emma.

“I remember my grandmother cooking smothered pork chops, pigtails, and spaghetti and meatballs, things like that, when we would stay with her,” says Green’s daughter, Malissa Fowler, who helps her mom out in the restaurant on weekends.

Green and her husband took over for her parents in 1979, after which it became harder to keep the grocery and dry goods part of the venture afloat. Big-box stores were beginning to shrivel the ability of neighborhood mom-and-pops to compete on price, Fowler says.

“It killed her to close the grocery,” Fowler says. “She held out as long as she could.”

The section where shelves once held Camellia beans, bags of rice and Wesson oil now has a handful of tables where diners take seats alone or in small groups, casually chit-chatting with each other. Green scurries back and forth from the serving line to the kitchen for emerging hot dishes. The distance from line to kitchen isn’t insignificant. The worn, whitewashed paint on the plywood floor confesses years of determined steps, nowadays taken in black Skechers. Culinary logisticians might advise a more efficient floor plan, but here’s betting Green wouldn’t listen. There’s comfort in repetitive tasks, well-earned in a spot open nearly 90 years.

Green takes orders by writing them on the outside of each Styrofoam clamshell, then filling it accordingly. After a few orders, she peels off the pair of latex gloves she’s been wearing, tossing it deftly across the room into an open trash can about 15 feet away. She heads to the kitchen to retrieve the pigtails, then dons a new pair of gloves before serving again. Meanwhile, the landline is ringing off the hook. Diners ask what’s on today’s menu, and the old-school front door bell chimes with entering patrons.

Along with daily specials, Owens also serves hamburgers, po-boys and a massive hybrid called the truck driver. A seasoned, hand-formed burger patty is grilled and topped with American cheese, and further adorned with grilled onions and peppers, iceberg lettuce and sliced tomato, pickles, ketchup and mayo.

Mac and cheese made with spaghetti, not elbow noodles; soft sweet peas; tender stewed cabbage; collard greens and candied yams are among the regular sides. Plump cornbread muffins rest in a separate pan, each a final adornment to a completed to-go box.

Green’s cooking has created fleets of regulars, but many patrons are lured back because of her enduring kindness, Fowler says.

“A lot of times, someone will come and say, ‘Where’s your mom?’ if they don’t see her and she’s in the back,” Fowler says. “They’ll just wait for her. She has that listening ear, and she gives advice. She’s a softie.”

At times, Green will also give away free lunches to neighborhood people in need, Fowler says.

Green shows no signs of slowing down. But if she were to retire, Fowler says she and her two sisters will keep the eatery open.

“That’s the hope,” Fowler says. “But before that, we need to get her to write her recipes down.”